|

|

| (383 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | ==Hydrogeophysical methods for characterization and monitoring of surface water-groundwater interactions== | + | ==Sediment Porewater Dialysis Passive Samplers for Inorganics (Peepers)== |

| − | Hydrogeophysical methods can be used to cost-effectively locate and characterize regions of

| + | Sediment porewater dialysis passive samplers, also known as “peepers,” are sampling devices that allow the measurement of dissolved inorganic ions in the porewater of a saturated sediment. Peepers function by allowing freely-dissolved ions in sediment porewater to diffuse across a micro-porous membrane towards water contained in an isolated compartment that has been inserted into sediment. Once retrieved after a deployment period, the resulting sample obtained can provide concentrations of freely-dissolved inorganic constituents in sediment, which provides measurements that can be used for understanding contaminant fate and risk. Peepers can also be used in the same manner in surface water, although this article is focused on the use of peepers in sediment. |

| − | enhanced groundwater/surface-water exchange (GWSWE) and to guide effective follow up investigations based on more traditional invasive methods. The most established methods exploit the contrasts in temperature and/or specific conductance that commonly exist between groundwater and surface water.

| + | |

| | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> |

| | | | |

| | '''Related Article(s):''' | | '''Related Article(s):''' |

| − | *[[Geophysical Methods]]

| |

| − | *[[Geophysical Methods - Case Studies]]

| |

| | | | |

| − | '''Contributor(s):'''

| + | *[[Contaminated Sediments - Introduction]] |

| − | *[[Dr. Lee Slater]] | + | *[[Contaminated Sediment Risk Assessment]] |

| − | *Dr. Ramona Iery | + | *[[In Situ Treatment of Contaminated Sediments with Activated Carbon]] |

| − | *Dr. Dimitrios Ntarlagiannis | + | *[[Passive Sampling of Munitions Constituents]] |

| − | *Henry Moore | + | *[[Sediment Capping]] |

| | + | *[[Mercury in Sediments]] |

| | + | *[[Passive Sampling of Sediments]] |

| | | | |

| − | '''Key Resource(s):'''

| |

| − | *USGS Method Selection Tool: https://code.usgs.gov/water/espd/hgb/gw-sw-mst

| |

| − | *USGS Water Resources: https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources/science/groundwatersurface-water-interaction

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==Introduction==

| + | '''Contributor(s):''' |

| − | Discharges of contaminated groundwater to surface water bodies threaten ecosystems and degrade the quality of surface water resources. Subsurface heterogeneity associated with the geological setting and stratigraphy often results in such discharges occurring as localized zones (or seeps) of contaminated groundwater. Traditional methods for investigating GWSWE include [https://books.gw-project.org/groundwater-surface-water-exchange/chapter/seepage-meters/#:~:text=Seepage%20meters%20measure%20the%20flux,that%20it%20isolates%20water%20exchange. seepage meters]<ref>Rosenberry, D. O., Duque, C., and Lee, D. R., 2020. History and Evolution of Seepage Meters for Quantifying Flow between Groundwater and Surface Water: Part 1 – Freshwater Settings. Earth-Science Reviews, 204(103167). [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103167 doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103167].</ref><ref>Duque, C., Russoniello, C. J., and Rosenberry, D. O., 2020. History and Evolution of Seepage Meters for Quantifying Flow between Groundwater and Surface Water: Part 2 – Marine Settings and Submarine Groundwater Discharge. Earth-Science Reviews, 204 ( 103168). [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103168 doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103168].</ref>, which directly quantify the volume flux crossing the bed of a surface water body (i.e, a lake, river or wetland) and point probes that locally measure key water quality parameters (e.g., temperature, pore water velocity, specific conductance, dissolved oxygen, pH). Seepage meters provide direct estimates of seepage fluxes between groundwater and surface- water but are time consuming and can be difficult to deploy in high energy surface water environments and along armored bed sediments. Manual seepage meters rely on quantifying volume changes in a bag of water that is hydraulically connected to the bed. Although automated seepage meters such as the [https://clu-in.org/programs/21m2/navytools/gsw/#ultraseep Ultraseep system] have been developed, they are generally not suitable for long term deployment (weeks to months). The US Navy has developed the [https://clu-in.org/programs/21m2/navytools/gsw/#trident Trident probe] for more rapid (relative to seepage meters) sampling, whereby the probe is inserted into the bed and point-in-time pore water quality and sediment parameters are directly recorded (note that the Trident probe does not measure a seepage flux). Such direct probe-based measurements are still relatively time consuming to acquire, particularly when reconnaissance information is required over large areas to determine the location of discrete seeps for further, more quantitative analysis.

| |

| | | | |

| − | Over the last few decades, a broader toolbox of hydrogeophysical technologies has been developed to rapidly and non-invasively evaluate zones of GWSWE in a variety of surface water settings, spanning from freshwater bodies to saline coastal environments. Many of these technologies are currently being deployed under a Department of Defense Environmental Security Technology Certification Program ([https://serdp-estcp.mil/ ESTCP]) project ([https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/e4a12396-4b56-4318-b9e5-143c3011b8ff ER21-5237]) to demonstrate the value of the toolbox to remedial program managers (RPMs) dealing with the challenge of characterizing surface water contamination via groundwater from facilities proximal to surface water bodies. This article summarizes these technologies and provides references to key resources, mostly provided by the [https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources Water Resources Mission Area] of the United States Geological Survey that describe the technologies in further detail.

| + | *Florent Risacher, M.Sc. |

| | + | *Jason Conder, Ph.D. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Hydrogeophysical Technologies for Understanding Groundwater-Surface Water Interactions==

| + | '''Key Resource(s):''' |

| − | [[Wikipedia: Hydrogeophysics |Hydrogeophysical technologies]] exploit contrasts in the physical properties between groundwater and surface water to detect and monitor zones of pronounced GWSWE. The two most valuable properties to measure are temperature and electrical conductivity. Temperature has been used for decades as an indicator of groundwater-surface water exchange<ref>Constantz, J., 2008. Heat as a Tracer to Determine Streambed Water Exchanges. Water Resources Research, 44 (4).[https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1029/2008WR006996 doi: 10.1029/2008WR006996].[https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1029/2008WR006996 Open Access Article]</ref> with early uses including pushing a thermistor into the bed of a surface water body to assess zones of surface water downwelling and groundwater upwelling. Today, a variety of novel technologies that measure temperature over a wide range of spatial and temporal scales are being used to investigate GWSWE. The evaluation of electrical conductivity measurements using point probes and geophysical imaging is also well-established. However, new technologies are now available to exploit electrical conductivity contrasts from GWSWE occurring over a range of spatial and temporal scales.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ===Temperature-Based Technologies===

| + | *A review of peeper passive sampling approaches to measure the availability of inorganics in sediment porewater<ref>Risacher, F.F., Schneider, H., Drygiannaki, I., Conder, J., Pautler, B.G., and Jackson, A.W., 2023. A Review of Peeper Passive Sampling Approaches to Measure the Availability of Inorganics in Sediment Porewater. Environmental Pollution, 328, Article 121581. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121581 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121581] [[Media: RisacherEtAl2023a.pdf | Open Access Manuscript]]</ref> |

| − | Several temperature-based GWSWE methodologies exploit the gradient in temperature between surface water and groundwater that exist during certain times of day or seasons of the year. The thermal insulation provided by the Earth’s land surface means that groundwater is warmer than surface water in winter months, but colder than surface water in summer months away from the equator. Therefore, in temperate climates, localized (or ‘preferential’) groundwater discharge into surface water bodies is often observed as cold temperature anomalies in the summer and warm temperature anomalies in the winter. However, there are times of the year such as fall and spring when contrasts in the temperature between groundwater and surface water will be minimal, or even undetectable. These seasonal-driven points in time correspond to the switch in the polarity of the temperature contrast between groundwater and surface water. Consequently, SW to GW gradient temperature-based methods are most effective when deployed at times of the year when the temperature contrasts between groundwater and surface water are greatest. Other time-series temperature monitoring methods depend more on natural daily signals measured at the bed interface and in bed sediments, and those signals may exist year round except where strongly muted by ice cover or surface water stratification. A variety of sensing technologies now exist within the GWSWE toolbox, from techniques that rapidly characterize temperature contrasts over large areas, down to powerful monitoring methods that can continuously quantify GWSWE fluxes at discrete locations identified as hotspots.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ====Characterization Methods==== | + | *Best Practices User’s Guide: Standardizing Sediment Porewater Passive Samplers for Inorganic Constituents of Concern<ref name="RisacherEtAl2023">Risacher, F.F., Nichols, E., Schneider, H., Lawrence, M., Conder, J., Sweett, A., Pautler, B.G., Jackson, W.A., Rosen, G., 2023b. Best Practices User’s Guide: Standardizing Sediment Porewater Passive Samplers for Inorganic Constituents of Concern, ESTCP ER20-5261. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/db871313-fbc0-4432-b536-40c64af3627f Project Website] [[Media: ER20-5261BPUG.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref> |

| − | The primary use of the characterization methods is to rapidly determine precise locations of groundwater upwelling over large areas in order to pinpoint locations for subsequent ground-based observations. A common limitation of these methods is that they can only sense groundwater fluxes into surface water. Methods applied at the water surface and in the surface water column generally cannot detect localized regions of surface water transfer to groundwater, for which temperature measurements collected within the bed sediments are needed. This is a more challenging characterization task that may, in the right conditions, be addressed using electrical conductivity-based methods described later in this article.

| |

| | | | |

| − | =====Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Infrared (UAV-IR)=====

| + | *[https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/db871313-fbc0-4432-b536-40c64af3627f/er20-5261-project-overview Standardizing Sediment Porewater Passive Samplers for Inorganic Constituents of Concern, ESTCP Project ER20-5261] |

| − | [[File:IeryFig1.png | thumb |600px|Figure 1. UAV IR orthomosaics with estimated scale of (a) a wetland in winter (modified from Briggs et al.<ref>Briggs, M. A., Jackson, K. E., Liu, F., Moore, E. M., Bisson, A., Helton, A. M., 2022. Exploring Local Riverbank Sediment Controls on the Occurrence of Preferential Groundwater Discharge Points. Water, 14(1). [https://doi.org/10.3390/w14010011 doi: 10.3390/w14010011] [https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/14/1/11 Open Access Article].</ref>) and (b) a mountain stream in summer (modified from Briggs et al.<ref>Briggs, M. A., Wang, C., Day-Lewis, F. D., Williams, K. H., Dong, W., Lane, J. W., 2019. Return Flows from Beaver Ponds Enhance Floodplain-to-River Metals Exchange in Alluvial Mountain Catchments. Science of the Total Environment, 685, pp. 357–369. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.371 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.371]. [https://pdf.sciencedirectassets.com/271800/1-s2.0-S0048969719X00273/1-s2.0-S0048969719324246/am.pdf?X-Amz-Security-Token=IQoJb3JpZ2luX2VjEE0aCXVzLWVhc3QtMSJGMEQCIBY8ykhAP941wHO1NKj8EmXG3btdpgX6HaUV9zAo0PCMAiACRjzV0D2lbFFwnhUzEqBupGsgX6DkK62ZIEvb%2B0irbiq8BQj2%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F8BEAUaDDA1OTAwMzU0Njg2NSIMPmS2kZBwKKMGD%2F6GKpAFaY6lOuHO%2B1RkV%2FL6NkK74dL6YJculUqyZJn9s09njF1L%2Bb4LgjH%2FbawysWGvGeuH%2FQtSgwqFM90MQ4grDiDQPHUjSEDNVuN2II%2BqPK4oqkjqxwTmC2AObe%2FMY1c45L2nshYodZwtROh6Hl8Jp4B4HoDPE9wx1fEw7DGmB%2Bj70q5PG7%2FUUo3rLl6BCMT%2FWKFGfZSaOmaD5nweVaTRBUbgSVIcmCQKshE28TkHFpmwY58YNO0GjaKHXMsBNciZ2DvIPAHMyA1iymB7UFcoBRDicZJUDZvvnJNGj1bTX9tEQ49yil7IWD22hKPHL5nSogssocX5rRXiIglVT%2BAzHsMMyxfVxfFGBsmmSGAVG9FAeRPgx1T%2FIOqNo%2FOuyV9G%2BVSt5boUg4HBaZSvW5JNkL5bFpaMlrUTpMF%2F6Bbq3Q6EsiZMaFF0JOS3rvX5dkDlfu7OzJDBuRBszYoq%2B4%2FLQGJypfmarz8ZHEzi3Qw85nYbT68UGNa%2BZ9lZQG%2B47mF6Nj11%2F%2Fu%2FDTZD1p4r9nskTevwkRE%2BL7q3OSbqFj4YvN6qsMBLb%2FM7K2xSmaots0YGisZ09fVJBetJ1ILZpN5wCbS%2F77uFeQoxYXGIwz84wyqSueP7qcj3BQ%2FMkZRbmVpokj3vtESlfHvcZV2Ntu95JM9hetE9F5azaZ%2F%2Fm3WTE2mgW48FCbFI09p%2F7%2FSJyEWl54lNG7%2F2y0AayedFUs75otJauCpNJtr2pF4sbAGfgiagA2%2BzeDatKnI7MDhMD0R27wvaVwEup6vkLmTaJh4P8bGFd01Fwj96gZIKESW6HfwGXMBMj%2FoJn3CYpcfVelPmDr6jTeSJapUJoWE8gQVFjWuISuD4PdHYtbiSBL%2Fjn5jPvGMwvrqrrQY6sgEtK%2Fo3hSElpY%2Be20Xj4eNAJ%2BFmkb5nASAJvtygtnSdoc%2FBHMv4U3Je92nbunzwAwXaVCZ8FBK1%2F2cmq3sYLNOyPEJrCNqAo0Lgf137RvhaJb7erYXXfL7UCz1hePrG3I3bgKkBRN5PD%2FSlu%2BSSEimoEn4kCyxoaNYI9QvymaTlHZJM0ueXCYprlRfMneJXxnEVyC3qlMsTMtcL%2B45koHZeeTQJUMXWJB%2BYQxNDmNM3ZHH4&X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Date=20240119T205045Z&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Expires=300&X-Amz-Credential=ASIAQ3PHCVTYV2JHRO6K%2F20240119%2Fus-east-1%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Signature=3befd4efcf96517aad4e02a2d76e82cd278f02be8a60a5136a4981889df64f00&hash=c0f70e64bfdb70375c685714475b258099c0d0b19a2a7a556e77182cc6cfac9c&host=68042c943591013ac2b2430a89b270f6af2c76d8dfd086a07176afe7c76c2c61&pii=S0048969719324246&tid=pdf-5d6462f0-c794-4158-b89d-2a1f5b96a226&sid=8b33666922432845420b6d75b151281148eegxrqa&type=client Open Access Manuscript]</ref>) that both capture multiscale groundwater discharge processes. Figure reproduced from Mangel et al.<ref>Mangel, A. R., Dawson, C. B., Rey, D. M., Briggs, M. A., 2022. Drone Applications in Hydrogeophysics: Recent Examples and a Vision for the Future. The Leading Edge, 41 (8), pp. 540–547. [https://doi.org/10.1190/tle41080540.1 doi: 10.1190/tle41080540].</ref>]]

| |

| − | [[Wikipedia: Unmanned aerial vehicle | Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs)]] equipped with thermal infrared (IR) cameras can provide a very powerful tool for rapidly determining zones of pronounced upwelling of groundwater to surface water. Large areas of can be covered with high spatial resolution. The information obtained can be used to rapidly define locations of focused groundwater upwelling and prioritize these for more intensive surface-based observations (Figure 1). As with all thermal methods, flights must be performed when adequate contrasts in temperature between surface water and groundwater are expected to exist. Not just time of year but, because of the effect of the diurnal temperature signal on surface water bodies, time of day might need to be considered in order to maximize the chance of success. Calibration of UAV-IR camera measurements against simultaneously acquired direct measurements of temperature is recommended to optimize the value of these datasets. UAV-IR methods will not work in all situations. One major limitation of the technology is that the temperature expression of groundwater upwelling must be manifested at the surface of the surface water body. Consequently, the technology will not detect relatively small discharges occurring beneath a relatively deep surface water layer, and thermal imaging over the water surface can be complicated by thermal IR reflection. The chances of success with UAV-IR will be strongest in regions of exposed banks or shallow water where there are no strong currents causing mixing (and thus dilution) of the upwelling groundwater temperature signals. UAV-IR methods will therefore likely be most successful close to shorelines of lakes/ponds, over shallow, low flow streams and rivers and in wetland environments. UAV-IR methods require a licensed pilot, and restrictions on the use of airspace may limit the application of this technology.

| |

| | | | |

| − | =====Handheld Thermal Infrared (TIR) Cameras===== | + | ==Introduction== |

| − | [[File:IeryFig2.png | thumb|left |600px|Figure 2. (a) A TIR camera set up to image groundwater discharges to surface water (b) TIR data inset on a visible light photograph. Cooler (blue) bank seepage groundwater is discharging into warmer (red) stream water (temperature scale in degrees). Both photographs courtesy of Martin Briggs USGS.]]

| + | Biologically available inorganic constituents associated with sediment toxicity can be quantified by measuring the freely-dissolved fraction of contaminants in the porewater<ref>Conder, J.M., Fuchsman, P.C., Grover, M.M., Magar, V.S., Henning, M.H., 2015. Critical review of mercury SQVs for the protection of benthic invertebrates. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 34(1), pp. 6-21. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.2769 doi: 10.1002/etc.2769] [[Media: ConderEtAl2015.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref name="ClevelandEtAl2017">Cleveland, D., Brumbaugh, W.G., MacDonald, D.D., 2017. A comparison of four porewater sampling methods for metal mixtures and dissolved organic carbon and the implications for sediment toxicity evaluations. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 36(11), pp. 2906-2915. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.3884 doi: 10.1002/etc.3884]</ref>. Classical sediment porewater analysis usually consists of collecting large volumes of bulk sediments which are then mechanically squeezed or centrifuged to produce a supernatant, or suction of porewater from intact sediment, followed by filtration and collection<ref name="GruzalskiEtAl2016">Gruzalski, J.G., Markwiese, J.T., Carriker, N.E., Rogers, W.J., Vitale, R.J., Thal, D.I., 2016. Pore Water Collection, Analysis and Evolution: The Need for Standardization. In: Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, Vol. 237, pp. 37–51. Springer. [https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-23573-8_2 doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-23573-8_2]</ref>. The extraction and measurement processes present challenges due to the heterogeneity of sediments, physical disturbance, high reactivity of some complexes, and interaction between the solid and dissolved phases, which can impact the measured concentration of dissolved inorganics<ref>Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M., Teasdale, P.R., Reible, D., Mondon, J., Bennett, W.W., Campbell, P.G.C., 2014. Passive Sampling Methods for Contaminated Sediments: State of the Science for Metals. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 10(2), pp. 179–196. [https://doi.org/10.1002/ieam.1502 doi: 10.1002/ieam.1502] [[Media: PeijnenburgEtAl2014.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>. For example, sampling disturbance can affect redox conditions<ref name="TeasdaleEtAl1995">Teasdale, P.R., Batley, G.E., Apte, S.C., Webster, I.T., 1995. Pore water sampling with sediment peepers. Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 14(6), pp. 250–256. [https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-9936(95)91617-2 doi: 10.1016/0165-9936(95)91617-2]</ref><ref>Schroeder, H., Duester, L., Fabricius, A.L., Ecker, D., Breitung, V., Ternes, T.A., 2020. Sediment water (interface) mobility of metal(loid)s and nutrients under undisturbed conditions and during resuspension. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 394, Article 122543. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122543 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122543] [[Media: SchroederEtAl2020.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>, which can lead to under or over representation of inorganic chemical concentrations relative to the true dissolved phase concentration in the sediment porewater<ref>Wise, D.E., 2009. Sampling techniques for sediment pore water in evaluation of reactive capping efficacy. Master of Science Thesis. University of New Hampshire Scholars’ Repository. 178 pages. [https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/502 Website] [[Media: Wise2009.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="GruzalskiEtAl2016"/>. |

| − | Hand-held thermal infrared (TIR) cameras are powerful tools for visual identification of localized seeps of upwelling groundwater. TIR cameras may be used to follow up on UAV-IR surveys to better characterize local seeps identified from the air using UAV-IR. Alternatively, a TIR camera is a valuable tool when performing initial walks of prospective study sites as they may quickly confirm the presence of suspected seeps. TIR cameras provide high resolution images that can define the structure of localized seeps and may provide valuable insights into the role of discrete features (e.g., fractures in rocks or pipes in soil) in determining seep morphology (Figure 2). Like UAV-IR, TIR provides primarily qualitative information (location, extent) of seeps and it only succeeds when there are adequate contrasts between groundwater and surface water that are expressed at the surface of the investigated water body or along bank sediments. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) has made extensive use of TIR cameras for studying groundwater/surface-water exchange.

| |

| − | | |

| − | =====Continuous Near-bed Temperature Sensing=====

| |

| − | When performing surveys from a boat a simple yet often powerful technology is continuous

| |

| − | near-bed temperature sensing, whereby a temperature probe is strategically suspended to float in the water column just above the bed or dragged along it. Compared to UAV-IR, this approach does not rely on upwelling groundwater being expressed as a temperature anomaly at the surface. The utility of the method can be enhanced when a specific conductance probe is co- located with the temperature probe so that anomalies in both temperature and specific conductance can be investigated.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ====Monitoring Methods====

| |

| − | Monitoring methods allow temperature signals to be recorded with high temporal resolution along the bed interface or within bank or bed sediments. These methods can capture temporal trends in GWSWE driven by variations in the hydraulic gradients around surface water bodies, as well as changes in [[Wikipedia: Hydraulic conductivity | hydraulic conductivity]] due to sedimentation, clogging, scour or microbial mass. If vertical profiles of bed temperature are collected, a range of analytical and numerical models can be applied to infer the vertical water flux rate and direction, similar to a seepage meter. These fluxes may vary as a function of season, rainfall events (enhanced during storm activity), tidal variability in coastal settings and due to engineered controls such as dam discharges. The methods can capture evidence of GWSWE that may not be detected during a single ‘characterization’ survey if the local hydraulic conditions at that point in time result in relatively weak hydraulic gradients.

| |

| − | | |

| − | =====Fiber-optic Distributed Temperature Sensing (FO-DTS)=====

| |

| − | [[File:IeryFig3.png | thumb|600px|Figure 3. (a) Basic concept of FO-DTS based on backscattering of light transmitted down a FO fiber (b) Example of riverbed temperature data acquired over time and space in relation to variation in river stage (black line) modified from Mwakanyamale et al.<ref>Mwakanyamale, K., Slater, L., Day-Lewis, F., Elwaseif, M., Johnson, C., 2012. Spatially Variable Stage-Driven Groundwater-Surface Water Interaction Inferred from Time-Frequency Analysis of Distributed Temperature Sensing Data. Geophysical Research Letters, 39(6). [https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GL050824 doi: 10.1029/2011GL050824]. [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1029/2011GL050824 Open Access Article]</ref> (c) spatial distribution of riverbed temperature and correlation coefficient (CC) between riverbed temperature and river stage for a 1.5 km stretch along the Hanford 300 Area adjacent to the Columbia River (modified from Slater et al.<ref name=”Slater2010”/>). Data are shown for winter and summer. Orange contours show uranium concentrations (μg/L) in groundwater measured in boreholes.]]

| |

| − | Fiber-optic distributed temperature sensing (FO-DTS) is a powerful monitoring technology used in fire detection, industrial process monitoring, and petroleum reservoir monitoring. The method is also used to obtain spatially rich datasets for monitoring GWSWE<ref name=”Selker2006”>Selker, J. S., Thévenaz, L., Huwald, H., Mallet, A., Luxemburg, W., van de Giesen, N., Stejskal, M., Zeman, J., Westhoff, M., Parlange, M. B., 2006. Distributed Fiber-Optic Temperature Sensing for Hydrologic Systems. Water Resources Research, 42 (12). [https://doi.org/10.1029/2006WR005326 doi: 10.1029/2006WR005326]. [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1029/2006WR005326 Open Access Article]</ref><ref name=”Tyler2009”>Tyler, S. W., Selker, J. S., Hausner, M. B., Hatch, C. E., Torgersen, T., Thodal, C. E., Schladow, S. G., 2009. Environmental Temperature Sensing Using Raman Spectra DTS Fiber-Optic Methods. Water Resources Research, 45(4). [https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1029/2008WR007052 doi: 10.1029/2008WR007052]. [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1029/2008WR007052 Open Access Article]</ref>. The sensor consists of standard telecommunications fiber-optic fiber typically housed in armored cable and the physics is based on temperature-dependent backscatter mechanisms including Brillouin and Raman backscatter<ref name=”Selker2006”/>. Most commercially available systems are based on analysis of Raman scatter. As laser light is transmitted down the fiber-optic cable, light scatters continuously back toward the instrument from all along the fiber, with some of the scattered light at frequencies above and below the frequency of incident light, i.e., anti-Stokes and Stokes-Raman backscatter, respectively. The ratio of anti-Stokes to Stokes energy provides the basis for FO-DTS measurements. Measurements are localized to a section of cable according to a time-of-flight calculation (i.e., optical time-domain reflectometry). Assuming the speed of light within the fiber is constant, scatter collected over a specific time window corresponds to a specific spatial interval of the fiber. Although there are tradeoffs between spatial resolution, thermal precision, and sampling time, in practice it is possible to achieve sub meter-scale spatial and approximate 0.1°C thermal precision for measurement cycle times on the order of minutes and cables extending several kilometers<ref name=”Tyler2009”/>; thus, thousands of temperature measurements can be made simultaneously along a single cable. The method allows the visualization of a large amount of temperature data and rapid identification of major trends in GWSWE. Figure 3 illustrates the use of FO-DTS to detect and monitor zones of focused groundwater discharge along a 1.5 km reach of the Columbia River that is threatened by contaminated groundwater<ref name=”Slater2010”>Slater, L. D., Ntarlagiannis, D., Day-Lewis, F. D., Mwakanyamale, K., Versteeg, R. J., Ward, A., Strickland, C., Johnson, C. D., Lane Jr., J. W., 2010. Use of Electrical Imaging and Distributed Temperature Sensing Methods to Characterize Surface Water-Groundwater Exchange Regulating Uranium Transport at the Hanford 300 Area, Washington. Water Resources Research, 46(10). [https://doi.org/10.1029/2010WR009110 doi: 10.1029/2010WR009110]. [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1029/2010WR009110 Open Access Article]</ref>. As temperature is only sensed at the cable on the bed, FO-DTS can only detect groundwater inputs to surface water. It cannot detect losses of surface water to groundwater. The USGS public domain software tool [https://www.usgs.gov/software/dtsgui DTSGUI] allows a user to import, manage, visualize and analyze FO-DTS datasets.

| |

| | | | |

| − | =====Vertical temperature profilers (VTPs)===== | + | To address the complications with mechanical porewater sampling, passive sampling approaches for inorganics have been developed to provide a method that has a low impact on the surrounding geochemistry of sediments and sediment porewater, thus enabling more precise measurements of inorganics<ref name="ClevelandEtAl2017"/>. Sediment porewater dialysis passive samplers, also known as “peepers,” were developed more than 45 years ago<ref name="Hesslein1976">Hesslein, R.H., 1976. An in situ sampler for close interval pore water studies. Limnology and Oceanography, 21(6), pp. 912-914. [https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1976.21.6.0912 doi: 10.4319/lo.1976.21.6.0912] [[Media: Hesslein1976.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref> and refinements to the method such as the use of reverse tracers have been made, improving the acceptance of the technology as decision making tool. |

| | | | |

| − | Analysis methods now allow for the accurate quantification of groundwater fluxes over time. Vertical temperature profilers (VTPs) are sensors applied for diurnal temperature data collection within saturated geologic matrices (Figure 4). Extensive experience with VTPs indicates that the methodology is equal to traditional seepage meters in terms of flux accuracy<ref>Hare, D. K., Briggs, M. A., Rosenberry, D. O., Boutt, D. F., Lane Jr., J. W., 2015. A Comparison of Thermal Infrared to Fiber-Optic Distributed Temperature Sensing for Evaluation of Groundwater Discharge to Surface Water. Journal of Hydrology, 530, pp. 153–166. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.09.059 doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.09.059].</ref>. However, VTPs have the advantage of measuring continuous temporal variations in flux rates while such information is impractical to obtain with traditional seepage meters.

| + | ==Peeper Designs== |

| − | [[File:IeryFig4.png |thumb|600px|left|Figure 4. (a) Schematic of different VTP setups including (from left to right) thermistors in a piezometer, thermistors embedded in a solid rod and wrapped FO-DTS cable modified from Irvine et al.<ref name=”Irvine2017a”/>; (b) construction of VTPs showing thermistors embedded in rods and subsequent insulation; (c) example dataset plotted in 1DTempPro showing 5 days of streambed temperature at 6 streambed depths<ref>Koch, F. W., Voytek, E. B., Day-Lewis, F. D., Healy, R., Briggs, M. A., Lane Jr., J. W., Werkema, D., 2016. 1DTempPro V2: New Features for Inferring Groundwater/Surface-Water Exchange. Groundwater, 54(3), pp. 434–439. [https://doi.org/10.1111/gwat.12369 doi: 10.1111/gwat.12369].</ref>.]] | + | [[File:RisacherFig1.png|thumb|300px|Figure 1. Conceptual illustration of peeper construction showing (top, left to right) the peeper cap (optional), peeper membrane and peeper chamber, and (bottom) an assembled peeper containing peeper water]] |

| | + | [[File:RisacherFig2.png | thumb |400px| Figure 2. Example of Hesslein<ref name="Hesslein1976"/> general peeper design (42 peeper chambers), from [https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/peeper-samplers USGS]]] |

| | + | [[File:RisacherFig3.png | thumb |400px| Figure 3. Peeper deployment structure to allow the measurement of metal availability in different sediment layers using five single-chamber peepers (Photo: Geosyntec Consultants)]] |

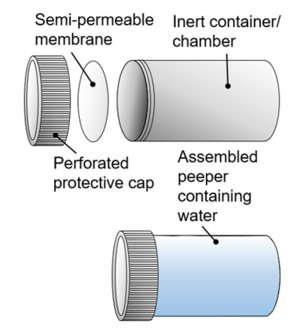

| | + | Peepers (Figure 1) are inert containers with a small volume (typically 1-100 mL) of purified water (“peeper water”) capped with a semi-permeable membrane. Peepers can be manufactured in a wide variety of formats (Figure 2, Figure 3) and deployed in in various ways. |

| | | | |

| − | The low-cost design, ease of data collection, and straightforward interpretation of the data using open-source software make VTP sensors increasingly attractive for quantifying flux rates. These sensors typically consist of at least two temperature loggers installed within a steel or plastic pipe filled with foam insulation<ref name=”Irvine2017a”>Irvine, D. J., Briggs, M. A., Cartwright, I., Scruggs, C. R., Lautz, L. K., 2016. Improved Vertical Streambed Flux Estimation Using Multiple Diurnal Temperature Methods in Series. Groundwater, 55(1), pp. 73-80. [https://doi.org/10.1111/gwat.12436 doi: 10.1111/gwat.12436].</ref> although the use of loggers installed in well screens or FO-DTS cable wrapped around a piezometer casing (for high vertical resolution data) are also possible (Figure 4a). Loggers are inserted into the insulated housing at different depths, typically starting from one centimeter within the geologic matrix of interest<ref name=”Irvine2017b”> Irvine, D. J., Briggs, M. A., Lautz, L. K., Gordon, R. P., McKenzie, J. M., Cartwright, I., 2017. Using Diurnal Temperature Signals to Infer Vertical Groundwater-Surface Water Exchange. Groundwater, 55(1), pp. 10–26. [https://doi.org/10.1111/gwat.12459 doi: 10.1111/gwat.12459]. [https://ngwa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/am-pdf/10.1111/gwat.12459 Open Access Manuscript]</ref>. Temperature loggers usually remain within the first 0.2-meters of the geologic matrix based on the observed limits of diurnal signal influence<ref>Briggs, M. A., Lautz, L. K., Buckley, S. F., Lane Jr., J. W., 2014. Practical Limitations on the Use of Diurnal Temperature Signals to Quantify Groundwater Upwelling. Journal of Hydrology, 519(B), pp. 1739–1751. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.09.030 doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.09.030].</ref>, though zones of strong surface water downwelling may necessitate deeper temperature data collection. Reliability of flux values generated from the temperature signal analysis is dependent in part on the temperature logger precision, VTP placement, sediment heterogeneity, flow direction, flow magnitude<ref name=”Irvine2017b”/>, and absence of macropore flow. Application of single dimension temperature-based fluid flux models assumes that all flow is vertical and therefore lateral flow within upwelling systems cannot be quantified using VTPs, emphasizing the importance of the VTP installation location over the active area of exchange<ref name=”Irvine2017b”/> at shallow depths. Thermal parameters of the geologic matrix where the VTP is installed can be measured using a thermal properties analyzer to record heat capacity and thermal conductivity for later analytical and numerical modeling.

| + | Two designs are commonly used for peepers. Frequently, the designs are close adaptations of the original multi-chamber Hesslein design<ref name="Hesslein1976"/> (Figure 2), which consists of an acrylic sampler body with multiple sample chambers machined into it. Peeper water inside the chambers is separated from the outside environment by a semi-permeable membrane, which is held in place by a top plate fixed to the sampler body using bolts or screws. An alternative design consists of single-chamber peepers constructed using a single sample vial with a membrane secured over the mouth of the vial, as shown in Figure 3, and applied in Teasdale ''et al.''<ref name="TeasdaleEtAl1995"/>, Serbst ''et al.''<ref>Serbst, J.R., Burgess, R.M., Kuhn, A., Edwards, P.A., Cantwell, M.G., Pelletier, M.C., Berry, W.J., 2003. Precision of dialysis (peeper) sampling of cadmium in marine sediment interstitial water. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 45(3), pp. 297–305. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s00244-003-0114-5 doi: 10.1007/s00244-003-0114-5]</ref>, Thomas and Arthur<ref name="ThomasArthur2010">Thomas, B., Arthur, M.A., 2010. Correcting porewater concentration measurements from peepers: Application of a reverse tracer. Limnology and Oceanography: Methods, 8(8), pp. 403–413. [https://doi.org/10.4319/lom.2010.8.403 doi: 10.4319/lom.2010.8.403] [[Media: ThomasArthur2010.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>, Passeport ''et al.''<ref>Passeport, E., Landis, R., Lacrampe-Couloume, G., Lutz, E.J., Erin Mack, E., West, K., Morgan, S., Lollar, B.S., 2016. Sediment Monitored Natural Recovery Evidenced by Compound Specific Isotope Analysis and High-Resolution Pore Water Sampling. Environmental Science and Technology, 50(22), pp. 12197–12204. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b02961 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b02961]</ref>, and Risacher ''et al.''<ref name="RisacherEtAl2023"/>. The vial is filled with deionized water, and the membrane is held in place using the vial cap or an o-ring. Individual vials are either directly inserted into sediment or are incorporated into a support structure to allow multiple single-chamber peepers to be deployed at once over a given depth profile (Figure 3). |

| | | | |

| − | Analytical and numerical solutions, used to solve or estimate the advection-conduction equation within the geologic matrix (bed sediments), continue to evolve to better quantify flux values over time. Analytical solutions to the heat transport equation are used to solve for flux values between sensor pairs from VTP datasets<ref name=”Gordon2012”>Gordon, R. P., Lautz, L. K., Briggs, M. A., McKenzie, J. M., 2012. Automated Calculation of Vertical Pore-Water Flux from Field Temperature Time Series Using the VFLUX Method and Computer Program. Journal of Hydrology, 420–421, pp. 142–158. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2011.11.053 doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2011.11.053].</ref><ref name=”Irvine2015”>Irvine, D. J., Lautz, L. K., Briggs, M. A., Gordon, R. P., McKenzie, J. M., 2015. Experimental Evaluation of the Applicability of Phase, Amplitude, and Combined Methods to Determine Water Flux and Thermal Diffusivity from Temperature Time Series Using VFLUX 2. Journal of Hydrology, 531(3), pp. 728–737. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.10.054 doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.10.054].</ref>. [https://data.usgs.gov/modelcatalog/model/a54608c5-ea6c-4d61-afc4-1ae851f46744 VFLUX] is an open-source MATLAB package that allows the user to solve for flux values from a VTP dataset using a variety of analytical solutions<ref name=”Gordon2012”/><ref name=”Irvine2015”/> based on the vertical propagation of diurnal temperature signals. Other emerging ‘spectral’ methods make use of a wide range of natural temperature signals to estimate vertical flux and bed sediment thermal diffusivity<ref>Sohn, R. A., Harris, R. N., 2021. Spectral Analysis of Vertical Temperature Profile Time-Series Data in Yellowstone Lake Sediments. Water Resources Research, 57(4), e2020WR028430. [https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR028430 doi: 10.1029/2020WR028430]. [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1029/2020WR028430 Open Access Article]</ref>. VFLUX analytical solutions are limited by subsurface heterogeneity and diurnal temperature signal strength<ref name=”Irvine2017b”/>. [https://data.usgs.gov/modelcatalog/model/82fe0c15-97f5-4f6a-b389-b90f9bad615e 1DTempPro] (Figure 4c) provides a graphical user interface (GUI) for numerical solutions to heat transport<ref>Koch, F. W., Voytek, E. B., Day-Lewis, F. D., Healy, R., Briggs, M. A., Werkema, D., Lane Jr., J. W., 2015. 1DTempPro: A Program for Analysis of Vertical One-Dimensional (1D) Temperature Profiles v2.0. U.S. Geological Survey Software Release. [http://dx.doi.org/10.5066/F76T0JQS doi: 10.5066/F76T0JQS]. [https://data.usgs.gov/modelcatalog/model/82fe0c15-97f5-4f6a-b389-b90f9bad615e Free Download from USGS]</ref> and does not depend on diurnal signals. Numerical models can produce more accurate flux estimates in the case of complex boundary conditions and abrupt changes in flux rates, but require significant user calibration efforts for longer time series<ref name=”McAliley2022”> McAliley, W. A., Day-Lewis, F. D., Rey, D., Briggs, M. A., Shapiro, A. M., Werkema, D., 2022. Application of Recursive Estimation to Heat Tracing for Groundwater/Surface-Water Exchange. Water Resources Research, 58(6), e2021WR030443. [https://doi.org/10.1029/2021WR030443 doi: 10.1029/2021WR030443]. [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1029/2021WR030443 Open Access Article]</ref>. A hybrid approach between the analytical and numerical solutions, known as [https://www.sciencebase.gov/catalog/item/60a55c71d34ea221ce48b9e7 tempest1d]<ref name=”McAliley2022”/> improves flux modeling with enhanced computational efficiency, resolution of abrupt changes, evaluation of complex boundary conditions, and uncertainty estimations with each step. This new state-space modeling approach uses recursive estimation techniques to automatically estimate highly dynamic vertical flux patterns ranging from sub-daily to seasonal time scales<ref name=”McAliley2022”/>.

| + | ==Peepers Preparation, Deployment and Retrieval== |

| | + | [[File:RisacherFig4.png | thumb |300px| Figure 4: Conceptual illustration of peeper passive sampling in a sediment matrix, showing peeper immediately after deployment (top) and after equilibration between the porewater and peeper chamber water (bottom)]] |

| | + | Peepers are often prepared in laboratories but are also commercially available in a variety of designs from several suppliers. Peepers are prepared by first cleaning all materials to remove even trace levels of metals before assembly. The water contained inside the peeper is sometimes deoxygenated, and in some cases the peeper is maintained in a deoxygenated atmosphere until deployment<ref>Carignan, R., St‐Pierre, S., Gachter, R., 1994. Use of diffusion samplers in oligotrophic lake sediments: Effects of free oxygen in sampler material. Limnology and Oceanography, 39(2), pp. 468-474. [https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1994.39.2.0468 doi: 10.4319/lo.1994.39.2.0468] [[Media: CarignanEtAl1994.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>. However, recent studies<ref name="RisacherEtAl2023"/> have shown that deoxygenation prior to deployment does not significantly impact sampling results due to oxygen rapidly diffusing out of the peeper during deployment. Once assembled, peepers are usually shipped in a protective bag inside a hard-case cooler for protection. |

| | | | |

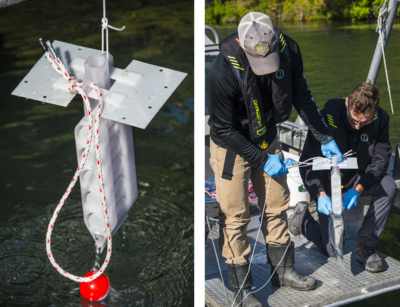

| | + | Peepers are deployed by insertion into sediment for a period of a few days to a few weeks. Insertion into the sediment can be achieved by wading to the location when the water depth is shallow, by using push poles for deeper deployments<ref name="RisacherEtAl2023"/>, or by professional divers for the deepest sites. If divers are used, an appropriate boat or ship will be required to accommodate the diver and their equipment. Whichever method is used, peepers should be attached to an anchor or a small buoy to facilitate retrieval at the end of the deployment period. |

| | | | |

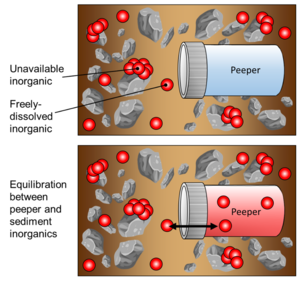

| | + | During deployment, passive sampling is achieved via diffusion of inorganics through the peeper’s semi-permeable membrane, as the enclosed volume of peeper water equilibrates with the surrounding sediment porewater (Figure 4). It is assumed that the peeper insertion does not greatly alter geochemical conditions that affect freely-dissolved inorganics. Additionally, it is assumed that the peeper water equilibrates with freely-dissolved inorganics in sediment in such a way that the concentration of inorganics in the peeper water would be equal to that of the concentration of inorganics in the sediment porewater. |

| | | | |

| − |

| + | After retrieval, the peepers are brought to the surface and usually preserved until they can be processed. This can be achieved by storing the peepers inside a sealable, airtight bag with either inert gas or oxygen absorbing packets<ref name="RisacherEtAl2023"/>. The peeper water can then be processed by quickly pipetting it into an appropriate sample bottle which usually contains a preservative (e.g., nitric acid for metals). This step is generally conducted in the field. Samples are stored on ice to maintain a temperature of less than 4°C and shipped to an analytical laboratory. The samples are then analyzed for inorganics by standard methods (i.e., USEPA SW-846). The results obtained from the analytical laboratory are then used directly or assessed using the equations below if a reverse tracer is used because deployment time is insufficient for all analytes to reach equilibrium. |

| | | | |

| − | Hydroquinones have been widely used as surrogates to understand the reductive transformation of NACs and MCs by NOM. Figure 4 shows the chemical structures of the singly deprotonated forms of four hydroquinone species previously used to study NAC/MC reduction. The second-order rate constants (''k<sub>R</sub>'') for the reduction of NACs/MCs by these hydroquinone species are listed in Table 1, along with the aqueous-phase one electron reduction potentials of the NACs/MCs (''E<sub>H</sub><sup>1’</sup>'') where available. ''E<sub>H</sub><sup>1’</sup>'' is an experimentally measurable thermodynamic property that reflects the propensity of a given NAC/MC to accept an electron in water (''E<sub>H</sub><sup>1</sup>''(R-NO<sub>2</sub>)):

| + | ==Equilibrium Determination (Tracers)== |

| | + | The equilibration period of peepers can last several weeks and depends on deployment conditions, analyte of interest, and peeper design. In many cases, it is advantageous to use pre-equilibrium methods that can use measurements in peepers deployed for shorter periods to predict concentrations at equilibrium<ref name="USEPA2017">USEPA, 2017. Laboratory, Field, and Analytical Procedures for Using Passive Sampling in the Evaluation of Contaminated Sediments: User’s Manual. EPA/600/R-16/357. [[Media: EPA_600_R-16_357.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>. |

| | | | |

| − | :::::<big>'''Equation 1:''' ''R-NO<sub>2</sub> + e<sup>-</sup> ⇔ R-NO<sub>2</sub><sup>•-</sup>''</big>

| + | Although the equilibrium concentration of an analyte in sediment can be evaluated by examining analyte results for peepers deployed for several different amounts of time (i.e., a time series), this is impractical for typical field investigations because it would require several mobilizations to the site to retrieve samplers. Alternately, reverse tracers (referred to as a performance reference compound when used with organic compound passive sampling) can be used to evaluate the percentage of equilibrium reached by a passive sampler. |

| | | | |

| − | Knowing the identity of and reaction order in the reductant is required to derive the second-order rate constants listed in Table 1. This same reason limits the utility of reduction rate constants measured with complex carbonaceous reductants such as NOM<ref name="Dunnivant1992"/>, BC<ref name="Oh2013"/><ref name="Oh2009"/><ref name="Xu2015"/><ref name="Xin2021">Xin, D., 2021. Understanding the Electron Storage Capacity of Pyrogenic Black Carbon: Origin, Redox Reversibility, Spatial Distribution, and Environmental Applications. Doctoral Thesis, University of Delaware. [https://udspace.udel.edu/bitstream/handle/19716/30105/Xin_udel_0060D_14728.pdf?sequence=1 Free download.]</ref>, and HS<ref name="Luan2010"/><ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2021"/>, whose chemical structures and redox moieties responsible for the reduction, as well as their abundance, are not clearly defined or known. In other words, the observed rate constants in those studies are specific to the experimental conditions (e.g., pH and NOM source and concentration), and may not be easily comparable to other studies.

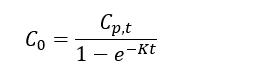

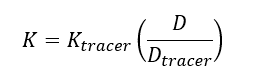

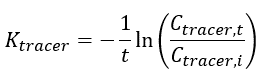

| + | Thomas and Arthur<ref name="ThomasArthur2010"/> studied the use of a reverse tracer to estimate percent equilibrium in lab experiments and a field application. They concluded that bromide can be used to estimate concentrations in porewater using measurements obtained before equilibrium is reached. Further studies were also conducted by Risacher ''et al.''<ref name="RisacherEtAl2023"/> showed that lithium can also be used as a tracer for brackish and saline environments. Both studies included a mathematical model for estimating concentrations of ions in external media (''C<small><sub>0</sub></small>'') based on measured concentrations in the peeper chamber (''C<small><sub>p,t</sub></small>''), the elimination rate of the target analyte (''K'') and the deployment time (''t''): |

| − | | + | </br> |

| − | {| class="wikitable mw-collapsible" style="float:left; margin-right:40px; text-align:center;"

| + | {| |

| − | |+ Table 1. Aqueous phase one electron reduction potentials and logarithm of second-order rate constants for the reduction of NACs and MCs by the singly deprotonated form of the hydroquinones lawsone, juglone, AHQDS and AHQS, with the second-order rate constants for the deprotonated NAC/MC species (i.e., nitrophenolates and NTO<sup>–</sup>) in parentheses.

| + | | || '''Equation 1:''' |

| − | |-

| + | | [[File: Equation1r.png]] |

| − | ! Compound

| |

| − | ! rowspan="2" |''E<sub>H</sub><sup>1'</sup>'' (V)

| |

| − | ! colspan="4"| Hydroquinone [log ''k<sub>R</sub>'' (M<sup>-1</sup>s<sup>-1</sup>)]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! (NAC/MC)

| |

| − | ! LAW<sup>-</sup>

| |

| − | ! JUG<sup>-</sup>

| |

| − | ! AHQDS<sup>-</sup>

| |

| − | ! AHQS<sup>-</sup>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | Nitrobenzene (NB) || -0.485<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.380<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -1.102<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 2.050<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || 3.060<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-nitrotoluene (2-NT) || -0.590<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -1.432<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -2.523<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.775<ref name="Hartenbach2008"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-nitrotoluene (3-NT) || -0.475<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.462<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -0.921<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-nitrotoluene (4-NT) || -0.500<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.041<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -1.292<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 1.822<ref name="Hartenbach2008"/> || 2.610<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-chloronitrobenzene (2-ClNB) || -0.485<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.342<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -0.824<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> ||2.412<ref name="Hartenbach2008"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-chloronitrobenzene (3-ClNB) || -0.405<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 1.491<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.114<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-chloronitrobenzene (4-ClNB) || -0.450<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 1.041<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -0.301<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 2.988<ref name="Hartenbach2008"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-acetylnitrobenzene (2-AcNB) || -0.470<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.519<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -0.456<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-acetylnitrobenzene (3-AcNB) || -0.405<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 1.663<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.398<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-acetylnitrobenzene (4-AcNB) || -0.360<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 2.519<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 1.477<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-nitrophenol (2-NP) || || 0.568 (0.079)<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) || || -0.699 (-1.301)<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-methyl-2-nitrophenol (4-Me-2-NP) || || 0.748 (0.176)<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-chloro-2-nitrophenol (4-Cl-2-NP) || || 1.602 (1.114)<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 5-fluoro-2-nitrophenol (5-Cl-2-NP) || || 0.447 (-0.155)<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) || -0.280<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/> || || 2.869<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || 5.204<ref name="Hartenbach2008"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-amino-4,6-dinitrotoluene (2-A-4,6-DNT) || -0.400<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/> || || 0.987<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-amino-2,6-dinitrotoluene (4-A-2,6-DNT) || -0.440<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/> || || 0.079<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2,4-diamino-6-nitrotoluene (2,4-DA-6-NT) || -0.505<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/> || || -1.678<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2,6-diamino-4-nitrotoluene (2,6-DA-4-NT) || -0.495<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/> || || -1.252<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |- | |

| − | | 1,3-dinitrobenzene (1,3-DNB) || -0.345<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || || 1.785<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |- | |

| − | | 1,4-dinitrobenzene (1,4-DNB) || -0.257<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || || 3.839<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-nitroaniline (2-NANE) || < -0.560<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || || -2.638<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-nitroaniline (3-NANE) || -0.500<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || || -1.367<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 1,2-dinitrobenzene (1,2-DNB) || -0.290<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || || || 5.407<ref name="Hartenbach2008"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-nitroanisole (4-NAN) || || -0.661<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || || 1.220<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> ||

| |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | 2-amino-4-nitroanisole (2-A-4-NAN) || || -0.924<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || || 1.150<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || 2.190<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> | + | | Where: || || |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | 4-amino-2-nitroanisole (4-A-2-NAN) || || || ||1.610<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || 2.360<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> | + | | || ''C<small><sub>0</sub></small>''|| is the freely dissolved concentration of the analyte in the sediment (mg/L or μg/L), sometimes referred to as ''C<small><sub>free</sub></small> |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | 2-chloro-4-nitroaniline (2-Cl-5-NANE) || || -0.863<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || || 1.250<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || 2.210<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> | + | | || ''C<small><sub>p,t</sub></small>'' || is the measured concentration of the analyte in the peeper at time of retrieval (mg/L or μg/L) |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | N-methyl-4-nitroaniline (MNA) || || -1.740<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || || -0.260<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || 0.692<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> | + | | || ''K'' || is the elimination rate of the target analyte |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (NTO) || || || || 5.701 (1.914)<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2021"/> || | + | | || ''t'' || is the deployment time (days) |

| − | |- | |

| − | | Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX) || || || || -0.349<ref name="Kwon2008"/> || | |

| | |} | | |} |

| | | | |

| − | [[File:AbioMCredFig5.png | thumb |500px|Figure 5. Relative reduction rate constants of the NACs/MCs listed in Table 1 for AHQDS<sup>–</sup>. Rate constants are compared with respect to RDX. Abbreviations of NACs/MCs as listed in Table 1.]]

| + | The elimination rate of the target analyte (''K'') is calculated using Equation 2: |

| − | Most of the current knowledge about MC degradation is derived from studies using NACs. The reduction kinetics of only four MCs, namely TNT, N-methyl-4-nitroaniline (MNA), NTO, and RDX, have been investigated with hydroquinones. Of these four MCs, only the reduction rates of MNA and TNT have been modeled<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/><ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/><ref name="Riefler2000">Riefler, R.G., and Smets, B.F., 2000. Enzymatic Reduction of 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene and Related Nitroarenes: Kinetics Linked to One-Electron Redox Potentials. Environmental Science and Technology, 34(18), pp. 3900–3906. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es991422f DOI: 10.1021/es991422f]</ref><ref name="Salter-Blanc2015">Salter-Blanc, A.J., Bylaska, E.J., Johnston, H.J., and Tratnyek, P.G., 2015. Predicting Reduction Rates of Energetic Nitroaromatic Compounds Using Calculated One-Electron Reduction Potentials. Environmental Science and Technology, 49(6), pp. 3778–3786. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es505092s DOI: 10.1021/es505092s] [https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/es505092s Open access article.]</ref>.

| + | </br> |

| − | | + | {| |

| − | Using the rate constants obtained with AHQDS<sup>–</sup>, a relative reactivity trend can be obtained (Figure 5). RDX is the slowest reacting MC in Table 1, hence it was selected to calculate the relative rates of reaction (i.e., log ''k<sub>NAC/MC</sub>'' – log ''k<sub>RDX</sub>''). If only the MCs in Figure 5 are considered, the reactivity spans 6 orders of magnitude following the trend: RDX ≈ MNA < NTO<sup>–</sup> < DNAN < TNT < NTO. The rate constant for DNAN reduction by AHQDS<sup>–</sup> is not yet published and hence not included in Table 1. Note that speciation of NACs/MCs can significantly affect their reduction rates. Upon deprotonation, the NAC/MC becomes negatively charged and less reactive as an oxidant (i.e., less prone to accept an electron). As a result, the second-order rate constant can decrease by 0.5-0.6 log unit in the case of nitrophenols and approximately 4 log units in the case of NTO (numbers in parentheses in Table 1)<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/><ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2021"/>.

| + | | || '''Equation 2:''' |

| − | | + | | [[File: Equation2r.png]] |

| − | ==Ferruginous Reductants==

| |

| − | {| class="wikitable mw-collapsible" style="float:right; margin-left:40px; text-align:center;"

| |

| − | |+ Table 2. Logarithm of second-order rate constants for reduction of NACs and MCs by dissolved Fe(II) complexes with the stoichiometry of ligand and iron in square brackets

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! rowspan="2" | Compound

| |

| − | ! rowspan="2" | E<sub>H</sub><sup>1'</sup> (V)

| |

| − | ! Cysteine<ref name="Naka2008"/></br>[FeL<sub>2</sub>]<sup>2-</sup>

| |

| − | ! Thioglycolic acid<ref name="Naka2008"/></br>[FeL<sub>2</sub>]<sup>2-</sup>

| |

| − | ! DFOB<ref name="Kim2009"/></br>[FeHL]<sup>0</sup>

| |

| − | ! AcHA<ref name="Kim2009"/></br>[FeL<sub>3</sub>]<sup>-</sup>

| |

| − | ! Tiron <sup>a</sup></br>[FeL<sub>2</sub>]<sup>6-</sup>

| |

| − | ! Fe-Porphyrin <sup>b</sup>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! colspan="6" | Fe(II)-Ligand [log ''k<sub>R</sub>'' (M<sup>-1</sup>s<sup>-1</sup>)]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | Nitrobenzene || -0.485<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -0.347 || 0.874 || 2.235 || -0.136 || 1.424<ref name="Gao2021">Gao, Y., Zhong, S., Torralba-Sanchez, T.L., Tratnyek, P.G., Weber, E.J., Chen, Y., and Zhang, H., 2021. Quantitative structure activity relationships (QSARs) and machine learning models for abiotic reduction of organic compounds by an aqueous Fe(II) complex. Water Research, 192, p. 116843. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2021.116843 DOI: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.116843]</ref></br>4.000<ref name="Salter-Blanc2015"/> || -0.018<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/></br>0.026<ref name="Salter-Blanc2015"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-nitrotoluene || -0.590<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || || || || || || -0.602<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-nitrotoluene || -0.475<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -0.434 || 0.767 || 2.106 || -0.229 || 1.999<ref name="Gao2021"/></br>3.800<ref name="Salter-Blanc2015"/> || 0.041<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-nitrotoluene || -0.500<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -0.652 || 0.528 || 2.013 || -0.402 || 1.446<ref name="Gao2021"/></br>3.500<ref name="Salter-Blanc2015"/> || -0.174<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-chloronitrobenzene || -0.485<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || || || || || || 0.944<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-chloronitrobenzene || -0.405<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.360 || 1.810 || 2.888 || 0.691 || 2.882<ref name="Gao2021"/></br>4.900<ref name="Salter-Blanc2015"/> || 0.724<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-chloronitrobenzene || -0.450<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.230 || 1.415 || 2.512 || 0.375 || 3.937<ref name="Gao2021"/></br>4.581<ref name="Naka2006"/> || 0.431<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/></br>0.289<ref name="Salter-Blanc2015"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-acetylnitrobenzene || -0.470<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || || || || || || 1.377<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-acetylnitrobenzene || -0.405<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || || || || || || 0.799<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-acetylnitrobenzene || -0.360<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.965 || 2.771 || || 1.872 || 5.028<ref name="Gao2021"/></br>6.300<ref name="Salter-Blanc2015"/> || 1.693<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/>

| |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | RDX || -0.550<ref name="Uchimiya2010">Uchimiya, M., Gorb, L., Isayev, O., Qasim, M.M., and Leszczynski, J., 2010. One-electron standard reduction potentials of nitroaromatic and cyclic nitramine explosives. Environmental Pollution, 158(10), pp. 3048–3053. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2010.06.033 DOI: 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.06.033]</ref> || || || || || 2.212<ref name="Gao2021"/></br>2.864<ref name="Kim2007"/> || | + | | Where: || || |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | HMX || -0.660<ref name="Uchimiya2010"/> || || || || || -2.762<ref name="Gao2021"/> || | + | | || ''K''|| is the elimination rate of the target analyte |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | TNT || -0.280<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/> || || || || || 7.427<ref name="Gao2021"/> || 2.050<ref name="Salter-Blanc2015"/> | + | | || ''K<small><sub>tracer</sub></small>'' || is the elimination rate of the tracer |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | 1,3-dinitrobenzene || -0.345<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || || || || || || 1.220<ref name="Salter-Blanc2015"/> | + | | || ''D'' || is the free water diffusivity of the analyte (cm<sup>2</sup>/s) |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | 2,4-dinitrotoluene || -0.380<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/> || || || || || 5.319<ref name="Gao2021"/> || 1.156<ref name="Salter-Blanc2015"/> | + | | || ''D<small><sub>tracer</sub></small>'' || is the free water diffusivity of the tracer (cm<sup>2</sup>/s) |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | Nitroguanidine (NQ) || -0.700<ref name="Uchimiya2010"/> || || || || || -0.185<ref name="Gao2021"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2,4-dinitroanisole (DNAN) || -0.400<ref name="Uchimiya2010"/> || || || || || || 1.243<ref name="Salter-Blanc2015"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="8" style="text-align:left; background-color:white;" | Notes:</br>''<sup>a</sup>'' 4,5-dihydroxybenzene-1,3-disulfonate (Tiron). ''<sup>b</sup>'' meso-tetra(N-methyl-pyridyl)iron porphin in cysteine.

| |

| | |} | | |} |

| − | {| class="wikitable mw-collapsible" style="float:left; margin-right:40px; text-align:center;" | + | |

| − | |+ Table 3. Rate constants for the reduction of MCs by iron minerals

| + | The elimination rate of the tracer (''K<small><sub>tracer</sub></small>'') is calculated using Equation 3: |

| | + | </br> |

| | + | {| |

| | + | | || '''Equation 3:''' |

| | + | | [[File: Equation3r2.png]] |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | ! MC

| + | | Where: || || |

| − | ! Iron Mineral

| |

| − | ! Iron mineral loading</br>(g/L)

| |

| − | ! Surface area</br>(m<sup>2</sup>/g)

| |

| − | ! Fe(II)<sub>aq</sub> initial</br>(mM) ''<sup>b</sup>''

| |

| − | ! Fe(II)<sub>aq</sub> after 24 h</br>(mM) ''<sup>c</sup>''

| |

| − | ! Fe(II)<sub>aq</sub> sorbed</br>(mM) ''<sup>d</sup>''

| |

| − | ! pH

| |

| − | ! Buffer

| |

| − | ! Buffer</br>(mM)

| |

| − | ! MC initial</br>(μM) ''<sup>e</sup>''

| |

| − | ! log ''k<sub>obs</sub>''</br>(h<sup>-1</sup>) ''<sup>f</sup>''

| |

| − | ! log ''k<sub>SA</sub>''</br>(Lh<sup>-1</sup>m<sup>-2</sup>) ''<sup>g</sup>''

| |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | TNT<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || Goethite || 0.64 || 17.5 || 1.5 || || || 7.0 || MOPS || 25 || 50 || 1.200 || 0.170 | + | | || ''K<small><sub>tracer</sub></small>'' || is the elimination rate of the tracer |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Gregory2004"/> || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 0.1 || 0 || 0.10 || 7.0 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -3.500 || -5.200 | + | | || ''C<small><sub>tracer,i</sub></small>''|| is the measured initial concentration of the tracer in the peeper prior to deployment (mg/L or μg/L) |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Gregory2004"/> || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 0.2 || 0.02 || 0.18 || 7.0 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -2.900 || -4.500 | + | | || ''C<small><sub>tracer,t</sub></small>'' || is the measured final concentration of the tracer in the peeper at time of retrieval (mg/L or μg/L) |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Gregory2004"/> || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 0.5 || 0.23 || 0.27 || 7.0 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -1.900 || -3.600 | + | | || ''t'' || is the deployment time (days) |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Gregory2004"/> || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 1.5 || 0.94 || 0.56 || 7.0 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -1.400 || -3.100

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Gregory2004"/> || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 3.0 || 1.74 || 1.26 || 7.0 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -1.200 || -2.900

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Gregory2004"/> || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 5.0 || 3.38 || 1.62 || 7.0 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -1.100 || -2.800

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Gregory2004"/> || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 10.0 || 7.77 || 2.23 || 7.0 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -1.000 || -2.600

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Gregory2004"/> || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 1.6 || 1.42 || 0.16 || 6.0 || MES || 50 || 50 || -2.700 || -4.300

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Gregory2004"/> || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 1.6 || 1.34 || 0.24 || 6.5 || MOPS || 50 || 50 || -1.800 || -3.400

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Gregory2004"/> || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 1.6 || 1.21 || 0.37 || 7.0 || MOPS || 50 || 50 || -1.200 || -2.900

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Gregory2004"/> || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 1.6 || 1.01 || 0.57 || 7.0 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -1.200 || -2.800

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Gregory2004"/> || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 1.6 || 0.76 || 0.82 || 7.5 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -0.490 || -2.100

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Gregory2004"/> || Magnetite || 1.00 || 44 || 1.6 || 0.56 || 1.01 || 8.0 || HEPES || 50 || 50 || -0.590 || -2.200

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NG<ref name="Oh2004"/> || Magnetite || 4.00 || 0.56|| 4.0 || || || 7.4 || HEPES || 90 || 226 || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NG<ref name="Oh2008"/> || Pyrite || 20.00 || 0.53 || || || || 7.4 || HEPES || 100 || 307 || -2.213 || -3.238

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | TNT<ref name="Oh2008"/> || Pyrite || 20.00 || 0.53 || || || || 7.4 || HEPES || 100 || 242 || -2.812 || -3.837

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Oh2008"/> || Pyrite || 20.00 || 0.53 || || || || 7.4 || HEPES || 100 || 201 || -3.058 || -4.083

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Larese-Casanova2008"/> || Carbonate Green Rust || 5.00 || 36 || || || || 7.0 || || || 100 || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Larese-Casanova2008"/> || Sulfate Green Rust || 5.00 || 20 || || || || 7.0 || || || 100 || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | DNAN<ref name="Khatiwada2018"/> || Sulfate Green Rust || 10.00 || || || || || 8.4 || || || 500 || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO<ref name="Khatiwada2018"/> || Sulfate Green Rust || 10.00 || || || || || 8.4 || || || 500 || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | DNAN<ref name="Berens2019"/> || Magnetite || 2.00 || 17.8 || 1.0 || || || 7.0 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 200 || -0.100 || -1.700

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | DNAN<ref name="Berens2019"/> || Mackinawite || 1.50 || || || || || 7.0 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 200 || 0.061 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | DNAN<ref name="Berens2019"/> || Goethite || 1.00 || 103.8 || 1.0 || || || 7.0 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 200 || 0.410 || -1.600

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Strehlau2018"/> || Magnetite || 0.62 || || 1.0 || || || 7.0 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 17.5 || -1.100 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Strehlau2018"/> || Magnetite || 0.62 || || || || || 7.0 || MOPS || 50 || 17.5 || -0.270 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Strehlau2018"/> || Magnetite || 0.62 || || 1.0 || || || 7.0 || MOPS || 10 || 17.6 || -0.480 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO<ref name="Cardenas-Hernandez2020"/> || Hematite || 1.00 || 5.7 || 1.0 || 0.92 || 0.08 || 5.5 || MES || 50 || 30 || -0.550 || -1.308

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO<ref name="Cardenas-Hernandez2020"/> || Hematite || 1.00 || 5.7 || 1.0 || 0.85 || 0.15 || 6.0 || MES || 50 || 30 || 0.619 || -0.140

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO<ref name="Cardenas-Hernandez2020"/> || Hematite || 1.00 || 5.7 || 1.0 || 0.9 || 0.10 || 6.5 || MES || 50 || 30 || 1.348 || 0.590

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO<ref name="Cardenas-Hernandez2020"/> || Hematite || 1.00 || 5.7 || 1.0 || 0.77 || 0.23 || 7.0 || MOPS || 50 || 30 || 2.167 || 1.408

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO<ref name="Cardenas-Hernandez2020"/> || Hematite ''<sup>a</sup>'' || 1.00 || 5.7 || || 1.01 || || 5.5 || MES || 50 || 30 || -1.444 || -2.200

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO<ref name="Cardenas-Hernandez2020"/> || Hematite ''<sup>a</sup>'' || 1.00 || 5.7 || || 0.97 || || 6.0 || MES || 50 || 30 || -0.658 || -1.413

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO<ref name="Cardenas-Hernandez2020"/> || Hematite ''<sup>a</sup>'' || 1.00 || 5.7 || || 0.87 || || 6.5 || MES || 50 || 30 || 0.068 || -0.688

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO<ref name="Cardenas-Hernandez2020"/> || Hematite ''<sup>a</sup>'' || 1.00 || 5.7 || || 0.79 || || 7.0 || MOPS || 50 || 30 || 1.210 || 0.456

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Tong2021"/> || Mackinawite || 0.45 || || || || || 6.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -0.092 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Tong2021"/> || Mackinawite || 0.45 || || || || || 7.0 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || 0.009 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Tong2021"/> || Mackinawite || 0.45 || || || || || 7.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || 0.158 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Tong2021"/> || Green Rust || 5 || || || || || 6.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -1.301 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Tong2021"/> || Green Rust || 5 || || || || || 7.0 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -1.097 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Tong2021"/> || Green Rust || 5 || || || || || 7.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -0.745 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Tong2021"/> || Goethite || 0.5 || || 1 || 1 || || 6.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -0.921 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Tong2021"/> || Goethite || 0.5 || || 1 || 1 || || 7.0 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -0.347 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Tong2021"/> || Goethite || 0.5 || || 1 || 1 || || 7.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || 0.009 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Tong2021"/> || Hematite || 0.5 || || 1 || 1 || || 6.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -0.824 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Tong2021"/> || Hematite || 0.5 || || 1 || 1 || || 7.0 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -0.456 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Tong2021"/> || Hematite || 0.5 || || 1 || 1 || || 7.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -0.237 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Tong2021"/> || Magnetite || 2 || || 1 || 1 || || 6.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -1.523 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Tong2021"/> || Magnetite || 2 || || 1 || 1 || || 7.0 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -0.824 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | RDX<ref name="Tong2021"/> || Magnetite || 2 || || 1 || 1 || || 7.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 10 || 250 || -0.229 ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | DNAN<ref name="Menezes2021"/> || Mackinawite || 4.28 || 0.25 || || || || 6.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 8.5 + 20% CO<sub>2</sub>(g) || 400 || 0.836 || 0.806

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | DNAN<ref name="Menezes2021"/> || Mackinawite || 4.28 || 0.25 || || || || 7.6 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 95.2 + 20% CO<sub>2</sub>(g) || 400 || 0.762 || 0.732

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | DNAN<ref name="Menezes2021"/> || Commercial FeS || 5.00 || 0.214 || || || || 6.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 8.5 + 20% CO<sub>2</sub>(g) || 400 || 0.477 || 0.447

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | DNAN<ref name="Menezes2021"/> || Commercial FeS || 5.00 || 0.214 || || || || 7.6 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 95.2 + 20% CO<sub>2</sub>(g) || 400 || 0.745 || 0.716

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO<ref name="Menezes2021"/> || Mackinawite || 4.28 || 0.25 || || || || 6.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 8.5 + 20% CO<sub>2</sub>(g) || 1000 || 0.663 || 0.633

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO<ref name="Menezes2021"/> || Mackinawite || 4.28 || 0.25 || || || || 7.6 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 95.2 + 20% CO<sub>2</sub>(g) || 1000 || 0.521 || 0.491

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO<ref name="Menezes2021"/> || Commercial FeS || 5.00 || 0.214 || || || || 6.5 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 8.5 + 20% CO<sub>2</sub>(g) || 1000 || 0.492 || 0.462

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NTO<ref name="Menezes2021"/> || Commercial FeS || 5.00 || 0.214 || || || || 7.6 || NaHCO<sub>3</sub> || 95.2 + 20% CO<sub>2</sub>(g) || 1000 || 0.427 || 0.398

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="13" style="text-align:left; background-color:white;" | Notes:</br>''<sup>a</sup>'' Dithionite-reduced hematite; experiments conducted in the presence of 1 mM sulfite. ''<sup>b</sup>'' Initial aqueous Fe(II); not added for Fe(II) bearing minerals. ''<sup>c</sup>'' Aqueous Fe(II) after 24h of equilibration. ''<sup>d</sup>'' Difference between b and c. ''<sup>e</sup>'' Initial nominal MC concentration. ''<sup>f</sup>'' Pseudo-first order rate constant. ''<sup>g</sup>'' Surface area normalized rate constant calculated as ''k<sub>Obs</sub>'' '''/''' (surface area concentration) or ''k<sub>Obs</sub>'' '''/''' (surface area × mineral loading).

| |

| − | |}

| |

| − | {| class="wikitable mw-collapsible" style="float:right; margin-left:40px; text-align:center;"

| |

| − | |+ Table 4. Rate constants for the reduction of NACs by iron oxides in the presence of aqueous Fe(II)

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! NAC ''<sup>a</sup>''

| |

| − | ! Iron Oxide

| |

| − | ! Iron oxide loading</br>(g/L)

| |

| − | ! Surface area</br>(m<sup>2</sup>/g)

| |

| − | ! Fe(II)<sub>aq</sub> initial</br>(mM) ''<sup>b</sup>''

| |

| − | ! Fe(II)<sub>aq</sub> after 24 h</br>(mM) ''<sup>c</sup>''

| |

| − | ! Fe(II)<sub>aq</sub> sorbed</br>(mM) ''<sup>d</sup>''

| |

| − | ! pH

| |

| − | ! Buffer

| |

| − | ! Buffer</br>(mM)

| |

| − | ! NAC initial</br>(μM) ''<sup>e</sup>''

| |

| − | ! log ''k<sub>obs</sub>''</br>(h<sup>-1</sup>) ''<sup>f</sup>''

| |

| − | ! log ''k<sub>SA</sub>''</br>(Lh<sup>-1</sup>m<sup>-2</sup>) ''<sup>g</sup>''

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | NB<ref name="Klausen1995"/> || Magnetite || 0.200 || 56.00 || 1.5000 || || || 7.00 || Phosphate || 10 || 50 || 1.05E+00 || 7.75E-04

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-ClNB<ref name="Klausen1995"/> || Magnetite || 0.200 || 56.00 || 1.5000 || || || 7.00 || Phosphate || 10 || 50 || 1.14E+00 || 8.69E-02

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-ClNB<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || Goethite || 0.640 || 17.50 || 1.5000 || || || 7.00 || MOPS || 25 || 50 || -1.01E-01 || -1.15E+00

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-ClNB<ref name="Elsner2004"/> || Goethite || 1.500 || 16.20 || 1.2400 || 0.9600 || 0.2800 || 7.20 || MOPS || 1.2 || 0.5 - 3 || 1.68E+00 || 2.80E-01

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-ClNB<ref name="Elsner2004"/> || Hematite || 1.800 || 13.70 || 1.0400 || 1.0100 || 0.0300 || 7.20 || MOPS || 1.2 || 0.5 - 3 || -2.32E+00 || -3.72E+00

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-ClNB<ref name="Elsner2004"/> || Lepidocrocite || 1.400 || 17.60 || 1.1400 || 1.0000 || 0.1400 || 7.20 || MOPS || 1.2 || 0.5 - 3 || 1.51E+00 || 1.20E-01

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-CNNB<ref name="Colón2006"/> || Ferrihydrite || 0.004 || 292.00 || 0.3750 || 0.3500 || 0.0300 || 7.97 || HEPES || 25 || 15 || -7.47E-01 || -8.61E-01

| |

| − | |-

| |