|

|

| (701 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | ==Hydrogeophysical methods for characterization and monitoring of surface water-groundwater interactions== | + | ==Lysimeters for Measuring PFAS Concentrations in the Vadose Zone== |

| − | Hydrogeophysical methods can be used to cost-effectively locate and characterize regions of

| + | [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) | PFAS]] are frequently introduced to the environment through soil surface applications which then transport through the vadose zone to reach underlying groundwater receptors. Due to their unique properties and resulting transport and retention behaviors, PFAS in the vadose zone can be a persistent contaminant source to underlying groundwater systems. Determining the fraction of PFAS present in the mobile porewater relative to the total concentrations in soils is critical to understanding the risk posed by PFAS in vadose zone source areas. Lysimeters are instruments that have been used by agronomists and vadose zone researchers for decades to determine water flux and solute concentrations in unsaturated porewater. Lysimeters have recently been developed as a critical tool for field investigations and characterizations of PFAS impacted source zones. |

| − | enhanced groundwater/surface-water exchange (GWSWE) and to guide effective follow up investigations based on more traditional invasive methods. The most established methods exploit the contrasts in temperature and/or specific conductance that commonly exist between groundwater and surface water.

| |

| | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> |

| | | | |

| | '''Related Article(s):''' | | '''Related Article(s):''' |

| − | *[[Geophysical Methods]]

| |

| − | *[[Geophysical Methods - Case Studies]]

| |

| | | | |

| − | '''Contributor(s):'''

| + | *[[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] |

| − | *[[Dr. Lee Slater]] | + | *[[PFAS Transport and Fate]] |

| − | *Dr. Ramona Iery | + | *[[PFAS Toxicology and Risk Assessment]] |

| − | *Dr. Dimitrios Ntarlagiannis | + | *[[Mass Flux and Mass Discharge]] |

| − | *Henry Moore

| |

| | | | |

| − | '''Key Resource(s):''' | + | '''Contributors:''' Dr. John F. Stults, Dr. Charles Schaefer |

| − | *USGS Method Selection Tool: https://code.usgs.gov/water/espd/hgb/gw-sw-mst | + | |

| − | *USGS Water Resources: https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources/science/groundwatersurface-water-interaction | + | '''Key Resources:''' |

| | + | *Assessment of PFAS in Collocated Soil and Porewater Samples at an AFFF-Impacted Source Zone: Field-Scale Validation of Suction Lysimeters<ref name="AndersonEtAl2022"/> |

| | + | *PFAS Concentrations in Soil versus Soil Porewater: Mass Distributions and the Impact of Adsorption at Air-Water Interfaces<ref name="BrusseauGuo2022"/> |

| | + | *Using Suction Lysimeters for Determining the Potential of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances to Leach from Soil to Groundwater: A Review<ref name="CostanzaEtAl2025"/> |

| | + | *Use of Lysimeters for Monitoring Soil Water Balance Parameters and Nutrient Leaching<ref name="MeissnerEtAl2020"/> |

| | + | *PFAS Porewater Concentrations in Unsaturated Soil: Field and Laboratory Comparisons Inform on PFAS Accumulation at Air-Water Interfaces<ref name="SchaeferEtAl2024"/> |

| | | | |

| | ==Introduction== | | ==Introduction== |

| − | Discharges of contaminated groundwater to surface water bodies threaten ecosystems and degrade the quality of surface water resources. Subsurface heterogeneity associated with the geological setting and stratigraphy often results in such discharges occurring as localized zones (or seeps) of contaminated groundwater. Traditional methods for investigating GWSWE include [https://books.gw-project.org/groundwater-surface-water-exchange/chapter/seepage-meters/#:~:text=Seepage%20meters%20measure%20the%20flux,that%20it%20isolates%20water%20exchange. seepage meters]<ref>Rosenberry, D. O., Duque, C., and Lee, D. R., 2020. History and Evolution of Seepage Meters for Quantifying Flow between Groundwater and Surface Water: Part 1 – Freshwater Settings. Earth-Science Reviews, 204(103167). [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103167 doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103167].</ref><ref>Duque, C., Russoniello, C. J., and Rosenberry, D. O., 2020. History and Evolution of Seepage Meters for Quantifying Flow between Groundwater and Surface Water: Part 2 – Marine Settings and Submarine Groundwater Discharge. Earth-Science Reviews, 204 ( 103168). [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103168 doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103168].</ref>, which directly quantify the volume flux crossing the bed of a surface water body (i.e, a lake, river or wetland) and point probes that locally measure key water quality parameters (e.g., temperature, pore water velocity, specific conductance, dissolved oxygen, pH). Seepage meters provide direct estimates of seepage fluxes between groundwater and surface- water but are time consuming and can be difficult to deploy in high energy surface water environments and along armored bed sediments. Manual seepage meters rely on quantifying volume changes in a bag of water that is hydraulically connected to the bed. Although automated seepage meters such as the [https://clu-in.org/programs/21m2/navytools/gsw/#ultraseep Ultraseep system] have been developed, they are generally not suitable for long term deployment (weeks to months). The US Navy has developed the [https://clu-in.org/programs/21m2/navytools/gsw/#trident Trident probe] for more rapid (relative to seepage meters) sampling, whereby the probe is inserted into the bed and point-in-time pore water quality and sediment parameters are directly recorded (note that the Trident probe does not measure a seepage flux). Such direct probe-based measurements are still relatively time consuming to acquire, particularly when reconnaissance information is required over large areas to determine the location of discrete seeps for further, more quantitative analysis.

| + | Lysimeters are devices that are placed in the subsurface above the groundwater table to monitor the movement of water through the soil<ref name="GossEhlers2009">Goss, M.J., Ehlers, W., 2009. The Role of Lysimeters in the Development of Our Understanding of Soil Water and Nutrient Dynamics in Ecosystems. Soil Use and Management, 25(3), pp. 213–223. [https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-2743.2009.00230.x doi: 10.1111/j.1475-2743.2009.00230.x]</ref><ref>Pütz, T., Fank, J., Flury, M., 2018. Lysimeters in Vadose Zone Research. Vadose Zone Journal, 17 (1), pp. 1-4. [https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2018.02.0035 doi: 10.2136/vzj2018.02.0035] [[Media: PutzEtAl2018.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref name="CostanzaEtAl2025">Costanza, J., Clabaugh, C.D., Leibli, C., Ferreira, J., Wilkin, R.T., 2025. Using Suction Lysimeters for Determining the Potential of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances to Leach from Soil to Groundwater: A Review. Environmental Science and Technology, 59(9), pp. 4215-4229. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.4c10246 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.4c10246]</ref>. Lysimeters have historically been used in agricultural sciences for monitoring nutrient or contaminant movement, soil moisture release curves, natural drainage patterns, and dynamics of plant-water interactions<ref name="GossEhlers2009"/><ref>Bergström, L., 1990. Use of Lysimeters to Estimate Leaching of Pesticides in Agricultural Soils. Environmental Pollution, 67 (4), 325–347. [https://doi.org/10.1016/0269-7491(90)90070-S doi: 10.1016/0269-7491(90)90070-S]</ref><ref>Dabrowska, D., Rykala, W., 2021. A Review of Lysimeter Experiments Carried Out on Municipal Landfill Waste. Toxics, 9(2), Article 26. [https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics9020026 doi: 10.3390/toxics9020026] [[Media: Dabrowska Rykala2021.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref>Fernando, S.U., Galagedara, L., Krishnapillai, M., Cuss, C.W., 2023. Lysimeter Sampling System for Optimal Determination of Trace Elements in Soil Solutions. Water, 15(18), Article 3277. [https://doi.org/10.3390/w15183277 doi: 10.3390/w15183277] [[Media: FernandoEtAl2023.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref name="MeissnerEtAl2020">Meissner, R., Rupp, H., Haselow, L., 2020. Use of Lysimeters for Monitoring Soil Water Balance Parameters and Nutrient Leaching. In: Climate Change and Soil Interactions. Elsevier, pp. 171-205. [https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818032-7.00007-2 doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-818032-7.00007-2]</ref><ref name="RogersMcConnell1993">Rogers, R.D., McConnell, J.W. Jr., 1993. Lysimeter Literature Review, Nuclear Regulatory Commission Report Numbers: NUREG/CR--6073, EGG--2706. [https://www.osti.gov/] ID: 10183270. [https://doi.org/10.2172/10183270 doi: 10.2172/10183270] [[Media: RogersMcConnell1993.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref>Sołtysiak, M., Rakoczy, M., 2019. An Overview of the Experimental Research Use of Lysimeters. Environmental and Socio-Economic Studies, 7(2), pp. 49-56. [https://doi.org/10.2478/environ-2019-0012 doi: 10.2478/environ-2019-0012] [[Media: SołtysiakRakoczy2019.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref name="Stannard1992">Stannard, D.I., 1992. Tensiometers—Theory, Construction, and Use. Geotechnical Testing Journal, 15(1), pp. 48-58. [https://doi.org/10.1520/GTJ10224J doi: 10.1520/GTJ10224J]</ref><ref name="WintonWeber1996">Winton, K., Weber, J.B., 1996. A Review of Field Lysimeter Studies to Describe the Environmental Fate of Pesticides. Weed Technology, 10(1), pp. 202-209. [https://doi.org/10.1017/S0890037X00045929 doi: 10.1017/S0890037X00045929]</ref>. Recently, there has been strong interest in the use of lysimeters to measure and monitor movement of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) through the vadose zone<ref name="Anderson2021">Anderson, R.H., 2021. The Case for Direct Measures of Soil-to-Groundwater Contaminant Mass Discharge at AFFF-Impacted Sites. Environmental Science and Technology, 55(10), pp. 6580-6583. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c01543 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c01543]</ref><ref name="AndersonEtAl2022">Anderson, R.H., Feild, J.B., Dieffenbach-Carle, H., Elsharnouby, O., Krebs, R.K., 2022. Assessment of PFAS in Collocated Soil and Porewater Samples at an AFFF-Impacted Source Zone: Field-Scale Validation of Suction Lysimeters. Chemosphere, 308(1), Article 136247. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136247 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136247]</ref><ref name="SchaeferEtAl2024">Schaefer, C.E., Nguyen, D., Fang, Y., Gonda, N., Zhang, C., Shea, S., Higgins, C.P., 2024. PFAS Porewater Concentrations in Unsaturated Soil: Field and Laboratory Comparisons Inform on PFAS Accumulation at Air-Water Interfaces. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology, 264, Article 104359. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconhyd.2024.104359 doi: 10.1016/j.jconhyd.2024.104359] [[Media: SchaeferEtAl2024.pdf | Open Access Manuscript]]</ref><ref name="SchaeferEtAl2023">Schaefer, C.E., Lavorgna, G.M., Lippincott, D.R., Nguyen, D., Schaum, A., Higgins, C.P., Field, J., 2023. Leaching of Perfluoroalkyl Acids During Unsaturated Zone Flushing at a Field Site Impacted with Aqueous Film Forming Foam. Environmental Science and Technology, 57(5), pp. 1940-1948. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c06903 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.2c06903]</ref><ref name="SchaeferEtAl2022">Schaefer, C.E., Lavorgna, G.M., Lippincott, D.R., Nguyen, D., Christie, E., Shea, S., O’Hare, S., Lemes, M.C.S., Higgins, C.P., Field, J., 2022. A Field Study to Assess the Role of Air-Water Interfacial Sorption on PFAS Leaching in an AFFF Source Area. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology, 248, Article 104001. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconhyd.2022.104001 doi: 10.1016/j.jconhyd.2022.104001] [[Media: SchaeferEtAl2022.pdf | Open Access Manuscript]]</ref><ref name="QuinnanEtAl2021">Quinnan, J., Rossi, M., Curry, P., Lupo, M., Miller, M., Korb, H., Orth, C., Hasbrouck, K., 2021. Application of PFAS-Mobile Lab to Support Adaptive Characterization and Flux-Based Conceptual Site Models at AFFF Releases. Remediation, 31(3), pp. 7-26. [https://doi.org/10.1002/rem.21680 doi: 10.1002/rem.21680]</ref>. PFAS are frequently introduced to the environment through land surface application and have been found to be strongly retained within the upper 5 feet of soil<ref name="BrusseauEtAl2020">Brusseau, M.L., Anderson, R.H., Guo, B., 2020. PFAS Concentrations in Soils: Background Levels versus Contaminated Sites. Science of The Total Environment, 740, Article 140017. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140017 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140017]</ref><ref name="BiglerEtAl2024">Bigler, M.C., Brusseau, M.L., Guo, B., Jones, S.L., Pritchard, J.C., Higgins, C.P., Hatton, J., 2024. High-Resolution Depth-Discrete Analysis of PFAS Distribution and Leaching for a Vadose-Zone Source at an AFFF-Impacted Site. Environmental Science and Technology, 58(22), pp. 9863-9874. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.4c01615 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.4c01615]</ref>. PFAS recalcitrance in the vadose zone means that environmental program managers and consultants need a cost-effective way of monitoring concentration conditions within the vadose zone. Repeated soil sampling and extraction processes are time consuming and only give a representative concentration of total PFAS in the matrix<ref name="NickersonEtAl2020">Nickerson, A., Maizel, A.C., Kulkarni, P.R., Adamson, D.T., Kornuc, J. J., Higgins, C.P., 2020. Enhanced Extraction of AFFF-Associated PFASs from Source Zone Soils. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(8), pp. 4952-4962. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c00792 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c00792]</ref>, not what is readily transportable in mobile porewater<ref name="SchaeferEtAl2023"/><ref name="StultsEtAl2024">Stults, J.F., Schaefer, C.E., Fang, Y., Devon, J., Nguyen, D., Real, I., Hao, S., Guelfo, J.L., 2024. Air-Water Interfacial Collapse and Rate-Limited Solid Desorption Control Perfluoroalkyl Acid Leaching from the Vadose Zone. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology, 265, Article 104382. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconhyd.2024.104382 doi: 10.1016/j.jconhyd.2024.104382] [[Media: StultsEtAl2024.pdf | Open Access Manuscript]]</ref><ref name="StultsEtAl2023">Stults, J.F., Choi, Y.J., Rockwell, C., Schaefer, C.E., Nguyen, D.D., Knappe, D.R.U., Illangasekare, T.H., Higgins, C.P., 2023. Predicting Concentration- and Ionic-Strength-Dependent Air–Water Interfacial Partitioning Parameters of PFASs Using Quantitative Structure–Property Relationships (QSPRs). Environmental Science and Technology, 57(13), pp. 5203-5215. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c07316 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.2c07316]</ref><ref name="BrusseauGuo2022">Brusseau, M.L., Guo, B., 2022. PFAS Concentrations in Soil versus Soil Porewater: Mass Distributions and the Impact of Adsorption at Air-Water Interfaces. Chemosphere, 302, Article 134938. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134938 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134938] [[Media: BrusseauGuo2022.pdf | Open Access Manuscript]]</ref>. Fortunately, lysimeters have been found to be a viable option for monitoring the concentration of PFAS in the mobile porewater phase in the vadose zone<ref name="Anderson2021"/><ref name="AndersonEtAl2022"/>. Note that while some lysimeters, known as weighing lysimeters, can directly measure water flux, the most commonly utilized lysimeters in PFAS investigations only provide measurements of porewater concentrations. |

| − | | |

| − | Over the last few decades, a broader toolbox of hydrogeophysical technologies has been developed to rapidly and non-invasively evaluate zones of GWSWE in a variety of surface water settings, spanning from freshwater bodies to saline coastal environments. Many of these technologies are currently being deployed under a Department of Defense Environmental Security Technology Certification Program ([https://serdp-estcp.mil/ ESTCP]) project ([https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/e4a12396-4b56-4318-b9e5-143c3011b8ff ER21-5237]) to demonstrate the value of the toolbox to remedial program managers (RPMs) dealing with the challenge of characterizing surface water contamination via groundwater from facilities proximal to surface water bodies. This article summarizes these technologies and provides references to key resources, mostly provided by the [https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources Water Resources Mission Area] of the United States Geological Survey that describe the technologies in further detail.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Hydrogeophysical Technologies for Understanding Groundwater-Surface Water Interactions==

| |

| − | [[Wikipedia: Hydrogeophysics |Hydrogeophysical technologies]] exploit contrasts in the physical properties between groundwater and surface water to detect and monitor zones of pronounced GWSWE. The two most valuable properties to measure are temperature and electrical conductivity. Temperature has been used for decades as an indicator of groundwater-surface water exchange<ref>Constantz, J., 2008. Heat as a Tracer to Determine Streambed Water Exchanges. Water Resources Research, 44 (4).[https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1029/2008WR006996 doi: 10.1029/2008WR006996].[https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1029/2008WR006996 Open Access Article]</ref> with early uses including pushing a thermistor into the bed of a surface water body to assess zones of surface water downwelling and groundwater upwelling. Today, a variety of novel technologies that measure temperature over a wide range of spatial and temporal scales are being used to investigate GWSWE. The evaluation of electrical conductivity measurements using point probes and geophysical imaging is also well-established. However, new technologies are now available to exploit electrical conductivity contrasts from GWSWE occurring over a range of spatial and temporal scales. | |

| − | | |

| − | ===Temperature-Based Technologies===

| |

| − | Several temperature-based GWSWE methodologies exploit the gradient in temperature between surface water and groundwater that exist during certain times of day or seasons of the year. The thermal insulation provided by the Earth’s land surface means that groundwater is warmer than surface water in winter months, but colder than surface water in summer months away from the equator. Therefore, in temperate climates, localized (or ‘preferential’) groundwater discharge into surface water bodies is often observed as cold temperature anomalies in the summer and warm temperature anomalies in the winter. However, there are times of the year such as fall and spring when contrasts in the temperature between groundwater and surface water will be minimal, or even undetectable. These seasonal-driven points in time correspond to the switch in the polarity of the temperature contrast between groundwater and surface water. Consequently, SW to GW gradient temperature-based methods are most effective when deployed at times of the year when the temperature contrasts between groundwater and surface water are greatest. Other time-series temperature monitoring methods depend more on natural daily signals measured at the bed interface and in bed sediments, and those signals may exist year round except where strongly muted by ice cover or surface water stratification. A variety of sensing technologies now exist within the GWSWE toolbox, from techniques that rapidly characterize temperature contrasts over large areas, down to powerful monitoring methods that can continuously quantify GWSWE fluxes at discrete locations identified as hotspots.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ====Characterization Methods====

| |

| − | The primary use of the characterization methods is to rapidly determine precise locations of groundwater upwelling over large areas in order to pinpoint locations for subsequent ground-based observations. A common limitation of these methods is that they can only sense groundwater fluxes into surface water. Methods applied at the water surface and in the surface water column generally cannot detect localized regions of surface water transfer to groundwater, for which temperature measurements collected within the bed sediments are needed. This is a more challenging characterization task that may, in the right conditions, be addressed using electrical conductivity-based methods described later in this article.

| |

| − | | |

| − | =====Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Infrared (UAV-IR)=====

| |

| − | [[File:IeryFig1.png | thumb |600px|Figure 1. UAV IR orthomosaics with estimated scale of (a) a wetland in winter (modified from Briggs et al.<ref>Briggs, M. A., Jackson, K. E., Liu, F., Moore, E. M., Bisson, A., Helton, A. M., 2022. Exploring Local Riverbank Sediment Controls on the Occurrence of Preferential Groundwater Discharge Points. Water, 14(1). [https://doi.org/10.3390/w14010011 doi: 10.3390/w14010011] [https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/14/1/11 Open Access Article].</ref>) and (b) a mountain stream in summer (modified from Briggs et al.<ref>Briggs, M. A., Wang, C., Day-Lewis, F. D., Williams, K. H., Dong, W., Lane, J. W., 2019. Return Flows from Beaver Ponds Enhance Floodplain-to-River Metals Exchange in Alluvial Mountain Catchments. Science of the Total Environment, 685, pp. 357–369. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.371 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.371]. [https://pdf.sciencedirectassets.com/271800/1-s2.0-S0048969719X00273/1-s2.0-S0048969719324246/am.pdf?X-Amz-Security-Token=IQoJb3JpZ2luX2VjEE0aCXVzLWVhc3QtMSJGMEQCIBY8ykhAP941wHO1NKj8EmXG3btdpgX6HaUV9zAo0PCMAiACRjzV0D2lbFFwnhUzEqBupGsgX6DkK62ZIEvb%2B0irbiq8BQj2%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F8BEAUaDDA1OTAwMzU0Njg2NSIMPmS2kZBwKKMGD%2F6GKpAFaY6lOuHO%2B1RkV%2FL6NkK74dL6YJculUqyZJn9s09njF1L%2Bb4LgjH%2FbawysWGvGeuH%2FQtSgwqFM90MQ4grDiDQPHUjSEDNVuN2II%2BqPK4oqkjqxwTmC2AObe%2FMY1c45L2nshYodZwtROh6Hl8Jp4B4HoDPE9wx1fEw7DGmB%2Bj70q5PG7%2FUUo3rLl6BCMT%2FWKFGfZSaOmaD5nweVaTRBUbgSVIcmCQKshE28TkHFpmwY58YNO0GjaKHXMsBNciZ2DvIPAHMyA1iymB7UFcoBRDicZJUDZvvnJNGj1bTX9tEQ49yil7IWD22hKPHL5nSogssocX5rRXiIglVT%2BAzHsMMyxfVxfFGBsmmSGAVG9FAeRPgx1T%2FIOqNo%2FOuyV9G%2BVSt5boUg4HBaZSvW5JNkL5bFpaMlrUTpMF%2F6Bbq3Q6EsiZMaFF0JOS3rvX5dkDlfu7OzJDBuRBszYoq%2B4%2FLQGJypfmarz8ZHEzi3Qw85nYbT68UGNa%2BZ9lZQG%2B47mF6Nj11%2F%2Fu%2FDTZD1p4r9nskTevwkRE%2BL7q3OSbqFj4YvN6qsMBLb%2FM7K2xSmaots0YGisZ09fVJBetJ1ILZpN5wCbS%2F77uFeQoxYXGIwz84wyqSueP7qcj3BQ%2FMkZRbmVpokj3vtESlfHvcZV2Ntu95JM9hetE9F5azaZ%2F%2Fm3WTE2mgW48FCbFI09p%2F7%2FSJyEWl54lNG7%2F2y0AayedFUs75otJauCpNJtr2pF4sbAGfgiagA2%2BzeDatKnI7MDhMD0R27wvaVwEup6vkLmTaJh4P8bGFd01Fwj96gZIKESW6HfwGXMBMj%2FoJn3CYpcfVelPmDr6jTeSJapUJoWE8gQVFjWuISuD4PdHYtbiSBL%2Fjn5jPvGMwvrqrrQY6sgEtK%2Fo3hSElpY%2Be20Xj4eNAJ%2BFmkb5nASAJvtygtnSdoc%2FBHMv4U3Je92nbunzwAwXaVCZ8FBK1%2F2cmq3sYLNOyPEJrCNqAo0Lgf137RvhaJb7erYXXfL7UCz1hePrG3I3bgKkBRN5PD%2FSlu%2BSSEimoEn4kCyxoaNYI9QvymaTlHZJM0ueXCYprlRfMneJXxnEVyC3qlMsTMtcL%2B45koHZeeTQJUMXWJB%2BYQxNDmNM3ZHH4&X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Date=20240119T205045Z&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Expires=300&X-Amz-Credential=ASIAQ3PHCVTYV2JHRO6K%2F20240119%2Fus-east-1%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Signature=3befd4efcf96517aad4e02a2d76e82cd278f02be8a60a5136a4981889df64f00&hash=c0f70e64bfdb70375c685714475b258099c0d0b19a2a7a556e77182cc6cfac9c&host=68042c943591013ac2b2430a89b270f6af2c76d8dfd086a07176afe7c76c2c61&pii=S0048969719324246&tid=pdf-5d6462f0-c794-4158-b89d-2a1f5b96a226&sid=8b33666922432845420b6d75b151281148eegxrqa&type=client Open Access Manuscript]</ref>) that both capture multiscale groundwater discharge processes. Figure reproduced from Mangel et al.<ref>Mangel, A. R., Dawson, C. B., Rey, D. M., Briggs, M. A., 2022. Drone Applications in Hydrogeophysics: Recent Examples and a Vision for the Future. The Leading Edge, 41 (8), pp. 540–547. [https://doi.org/10.1190/tle41080540.1 doi: 10.1190/tle41080540].</ref>]]

| |

| − | [[Wikipedia: Unmanned aerial vehicle | Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs)]] equipped with thermal infrared (IR) cameras can provide a very powerful tool for rapidly determining zones of pronounced upwelling of groundwater to surface water. Large areas of can be covered with high spatial resolution. The information obtained can be used to rapidly define locations of focused groundwater upwelling and prioritize these for more intensive surface-based observations (Figure 1). As with all thermal methods, flights must be performed when adequate contrasts in temperature between surface water and groundwater are expected to exist. Not just time of year but, because of the effect of the diurnal temperature signal on surface water bodies, time of day might need to be considered in order to maximize the chance of success. Calibration of UAV-IR camera measurements against simultaneously acquired direct measurements of temperature is recommended to optimize the value of these datasets. UAV-IR methods will not work in all situations. One major limitation of the technology is that the temperature expression of groundwater upwelling must be manifested at the surface of the surface water body. Consequently, the technology will not detect relatively small discharges occurring beneath a relatively deep surface water layer, and thermal imaging over the water surface can be complicated by thermal IR reflection. The chances of success with UAV-IR will be strongest in regions of exposed banks or shallow water where there are no strong currents causing mixing (and thus dilution) of the upwelling groundwater temperature signals. UAV-IR methods will therefore likely be most successful close to shorelines of lakes/ponds, over shallow, low flow streams and rivers and in wetland environments. UAV-IR methods require a licensed pilot, and restrictions on the use of airspace may limit the application of this technology.

| |

| − | | |

| − | =====Handheld Thermal Infrared (TIR) Cameras=====

| |

| − | [[File:IeryFig2.png | thumb|left |600px|Figure 2. (a) A TIR camera set up to image groundwater discharges to surface water (b) TIR data inset on a visible light photograph. Cooler (blue) bank seepage groundwater is discharging into warmer (red) stream water (temperature scale in degrees). Both photographs courtesy of Martin Briggs USGS.]] | |

| − | Hand-held thermal infrared (TIR) cameras are powerful tools for visual identification of localized seeps of upwelling groundwater. TIR cameras may be used to follow up on UAV-IR surveys to better characterize local seeps identified from the air using UAV-IR. Alternatively, a TIR camera is a valuable tool when performing initial walks of prospective study sites as they may quickly confirm the presence of suspected seeps. TIR cameras provide high resolution images that can define the structure of localized seeps and may provide valuable insights into the role of discrete features (e.g., fractures in rocks or pipes in soil) in determining seep morphology (Figure 2). Like UAV-IR, TIR provides primarily qualitative information (location, extent) of seeps and it only succeeds when there are adequate contrasts between groundwater and surface water that are expressed at the surface of the investigated water body or along bank sediments. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) has made extensive use of TIR cameras for studying groundwater/surface-water exchange.

| |

| − | | |

| − | =====Continuous Near-bed Temperature Sensing=====

| |

| − | When performing surveys from a boat a simple yet often powerful technology is continuous

| |

| − | near-bed temperature sensing, whereby a temperature probe is strategically suspended to float in the water column just above the bed or dragged along it. Compared to UAV-IR, this approach does not rely on upwelling groundwater being expressed as a temperature anomaly at the surface. The utility of the method can be enhanced when a specific conductance probe is co- located with the temperature probe so that anomalies in both temperature and specific conductance can be investigated.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ====Monitoring Methods====

| |

| − | Monitoring methods allow temperature signals to be recorded with high temporal resolution along the bed interface or within bank or bed sediments. These methods can capture temporal trends in GWSWE driven by variations in the hydraulic gradients around surface water bodies, as well as changes in [[Wikipedia: Hydraulic conductivity | hydraulic conductivity]] due to sedimentation, clogging, scour or microbial mass. If vertical profiles of bed temperature are collected, a range of analytical and numerical models can be applied to infer the vertical water flux rate and direction, similar to a seepage meter. These fluxes may vary as a function of season, rainfall events (enhanced during storm activity), tidal variability in coastal settings and due to engineered controls such as dam discharges. The methods can capture evidence of GWSWE that may not be detected during a single ‘characterization’ survey if the local hydraulic conditions at that point in time result in relatively weak hydraulic gradients.

| |

| − | | |

| − | =====Fiber-optic Distributed Temperature Sensing (FO-DTS)=====

| |

| − | [[File:IeryFig3.png | thumb|600px|Figure 3. (a) Basic concept of FO-DTS based on backscattering of light transmitted down a FO fiber (b) Example of riverbed temperature data acquired over time and space in relation to variation in river stage (black line) modified from Mwakanyamale et al.<ref>Mwakanyamale, K., Slater, L., Day-Lewis, F., Elwaseif, M., Johnson, C., 2012. Spatially Variable Stage-Driven Groundwater-Surface Water Interaction Inferred from Time-Frequency Analysis of Distributed Temperature Sensing Data. Geophysical Research Letters, 39(6). [https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GL050824 doi: 10.1029/2011GL050824]. [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1029/2011GL050824 Open Access Article]</ref> (c) spatial distribution of riverbed temperature and correlation coefficient (CC) between riverbed temperature and river stage for a 1.5 km stretch along the Hanford 300 Area adjacent to the Columbia River (modified from Slater et al.<ref name=”Slater2010”/>). Data are shown for winter and summer. Orange contours show uranium concentrations (μg/L) in groundwater measured in boreholes.]] | |

| − | Fiber-optic distributed temperature sensing (FO-DTS) is a powerful monitoring technology used in fire detection, industrial process monitoring, and petroleum reservoir monitoring. The method is also used to obtain spatially rich datasets for monitoring GWSWE<ref name=”Selker2006”>Selker, J. S., Thévenaz, L., Huwald, H., Mallet, A., Luxemburg, W., van de Giesen, N., Stejskal, M., Zeman, J., Westhoff, M., Parlange, M. B., 2006. Distributed Fiber-Optic Temperature Sensing for Hydrologic Systems. Water Resources Research, 42 (12). [https://doi.org/10.1029/2006WR005326 doi: 10.1029/2006WR005326]. [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1029/2006WR005326 Open Access Article]</ref><ref name=”Tyler2009”>Tyler, S. W., Selker, J. S., Hausner, M. B., Hatch, C. E., Torgersen, T., Thodal, C. E., Schladow, S. G., 2009. Environmental Temperature Sensing Using Raman Spectra DTS Fiber-Optic Methods. Water Resources Research, 45(4). [https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1029/2008WR007052 doi: 10.1029/2008WR007052]. [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1029/2008WR007052 Open Access Article]</ref>. The sensor consists of standard telecommunications fiber-optic fiber typically housed in armored cable and the physics is based on temperature-dependent backscatter mechanisms including Brillouin and Raman backscatter<ref name=”Selker2006”/>. Most commercially available systems are based on analysis of Raman scatter. As laser light is transmitted down the fiber-optic cable, light scatters continuously back toward the instrument from all along the fiber, with some of the scattered light at frequencies above and below the frequency of incident light, i.e., anti-Stokes and Stokes-Raman backscatter, respectively. The ratio of anti-Stokes to Stokes energy provides the basis for FO-DTS measurements. Measurements are localized to a section of cable according to a time-of-flight calculation (i.e., optical time-domain reflectometry). Assuming the speed of light within the fiber is constant, scatter collected over a specific time window corresponds to a specific spatial interval of the fiber. Although there are tradeoffs between spatial resolution, thermal precision, and sampling time, in practice it is possible to achieve sub meter-scale spatial and approximate 0.1°C thermal precision for measurement cycle times on the order of minutes and cables extending several kilometers<ref name=”Tyler2009”/>; thus, thousands of temperature measurements can be made simultaneously along a single cable. The method allows the visualization of a large amount of temperature data and rapid identification of major trends in GWSWE. Figure 3 illustrates the use of FO-DTS to detect and monitor zones of focused groundwater discharge along a 1.5 km reach of the Columbia River that is threatened by contaminated groundwater<ref name=”Slater2010”>Slater, L. D., Ntarlagiannis, D., Day-Lewis, F. D., Mwakanyamale, K., Versteeg, R. J., Ward, A., Strickland, C., Johnson, C. D., Lane Jr., J. W., 2010. Use of Electrical Imaging and Distributed Temperature Sensing Methods to Characterize Surface Water-Groundwater Exchange Regulating Uranium Transport at the Hanford 300 Area, Washington. Water Resources Research, 46(10). [https://doi.org/10.1029/2010WR009110 doi: 10.1029/2010WR009110]. [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1029/2010WR009110 Open Access Article]</ref>. As temperature is only sensed at the cable on the bed, FO-DTS can only detect groundwater inputs to surface water. It cannot detect losses of surface water to groundwater. The USGS public domain software tool [https://www.usgs.gov/software/dtsgui DTSGUI] allows a user to import, manage, visualize and analyze FO-DTS datasets.

| |

| − | | |

| − | =====Vertical temperature profilers (VTPs)=====

| |

| − | Analysis methods now allow for the accurate quantification of groundwater fluxes over time. Vertical temperature profilers (VTPs) are sensors applied for diurnal temperature data collection within saturated geologic matrices (Figure 4). Extensive experience with VTPs indicates that the methodology is equal to traditional seepage meters in terms of flux accuracy<ref>Hare, D. K., Briggs, M. A., Rosenberry, D. O., Boutt, D. F., Lane Jr., J. W., 2015. A Comparison of Thermal Infrared to Fiber-Optic Distributed Temperature Sensing for Evaluation of Groundwater Discharge to Surface Water. Journal of Hydrology, 530, pp. 153–166. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.09.059 doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.09.059].</ref>. However, VTPs have the advantage of measuring continuous temporal variations in flux rates while such information is impractical to obtain with traditional seepage meters.

| |

| − | [[File:IeryFig4.png |thumb|600px|left|Figure 4. (a) Schematic of different VTP setups including (from left to right) thermistors in a piezometer, thermistors embedded in a solid rod and wrapped FO-DTS cable modified from Irvine et al.<ref name=”Irvine2017a”/>; (b) construction of VTPs showing thermistors embedded in rods and subsequent insulation; (c) example dataset plotted in 1DTempPro showing 5 days of streambed temperature at 6 streambed depths<ref>Koch, F. W., Voytek, E. B., Day-Lewis, F. D., Healy, R., Briggs, M. A., Lane Jr., J. W., Werkema, D., 2016. 1DTempPro V2: New Features for Inferring Groundwater/Surface-Water Exchange. Groundwater, 54(3), pp. 434–439. [https://doi.org/10.1111/gwat.12369 doi: 10.1111/gwat.12369].</ref>.]]

| |

| − | | |

| − | The low-cost design, ease of data collection, and straightforward interpretation of the data using open-source software make VTP sensors increasingly attractive for quantifying flux rates. These sensors typically consist of at least two temperature loggers installed within a steel or plastic pipe filled with foam insulation<ref name=”Irvine2017a”>Irvine, D. J., Briggs, M. A., Cartwright, I., Scruggs, C. R., Lautz, L. K., 2016. Improved Vertical Streambed Flux Estimation Using Multiple Diurnal Temperature Methods in Series. Groundwater, 55(1), pp. 73-80. [https://doi.org/10.1111/gwat.12436 doi: 10.1111/gwat.12436].</ref> although the use of loggers installed in well screens or FO-DTS cable wrapped around a piezometer casing (for high vertical resolution data) are also possible (Figure 4a). Loggers are inserted into the insulated housing at different depths, typically starting from one centimeter within the geologic matrix of interest<ref name=”Irvine2017b”> Irvine, D. J., Briggs, M. A., Lautz, L. K., Gordon, R. P., McKenzie, J. M., Cartwright, I., 2017. Using Diurnal Temperature Signals to Infer Vertical Groundwater-Surface Water Exchange. Groundwater, 55(1), pp. 10–26. [https://doi.org/10.1111/gwat.12459 doi: 10.1111/gwat.12459]. [https://ngwa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/am-pdf/10.1111/gwat.12459 Open Access Manuscript]</ref>. Temperature loggers usually remain within the first 0.2-meters of the geologic matrix based on the observed limits of diurnal signal influence<ref>Briggs, M. A., Lautz, L. K., Buckley, S. F., Lane Jr., J. W., 2014. Practical Limitations on the Use of Diurnal Temperature Signals to Quantify Groundwater Upwelling. Journal of Hydrology, 519(B), pp. 1739–1751. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.09.030 doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.09.030].</ref>, though zones of strong surface water downwelling may necessitate deeper temperature data collection. Reliability of flux values generated from the temperature signal analysis is dependent in part on the temperature logger precision, VTP placement, sediment heterogeneity, flow direction, flow magnitude<ref name=”Irvine2017b”/>, and absence of macropore flow. Application of single dimension temperature-based fluid flux models assumes that all flow is vertical and therefore lateral flow within upwelling systems cannot be quantified using VTPs, emphasizing the importance of the VTP installation location over the active area of exchange<ref name=”Irvine2017b”/> at shallow depths. Thermal parameters of the geologic matrix where the VTP is installed can be measured using a thermal properties analyzer to record heat capacity and thermal conductivity for later analytical and numerical modeling.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Analytical and numerical solutions, used to solve or estimate the advection-conduction equation within the geologic matrix (bed sediments), continue to evolve to better quantify flux values over time. Analytical solutions to the heat transport equation are used to solve for flux values between sensor pairs from VTP datasets<ref name=”Gordon2012”>Gordon, R. P., Lautz, L. K., Briggs, M. A., McKenzie, J. M., 2012. Automated Calculation of Vertical Pore-Water Flux from Field Temperature Time Series Using the VFLUX Method and Computer Program. Journal of Hydrology, 420–421, pp. 142–158. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2011.11.053 doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2011.11.053].</ref><ref name=”Irvine2015”>Irvine, D. J., Lautz, L. K., Briggs, M. A., Gordon, R. P., McKenzie, J. M., 2015. Experimental Evaluation of the Applicability of Phase, Amplitude, and Combined Methods to Determine Water Flux and Thermal Diffusivity from Temperature Time Series Using VFLUX 2. Journal of Hydrology, 531(3), pp. 728–737. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.10.054 doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.10.054].</ref>. [https://data.usgs.gov/modelcatalog/model/a54608c5-ea6c-4d61-afc4-1ae851f46744 VFLUX] is an open-source MATLAB package that allows the user to solve for flux values from a VTP dataset using a variety of analytical solutions<ref name=”Gordon2012”/><ref name=”Irvine2015”/> based on the vertical propagation of diurnal temperature signals. Other emerging ‘spectral’ methods make use of a wide range of natural temperature signals to estimate vertical flux and bed sediment thermal diffusivity<ref>Sohn, R. A., Harris, R. N., 2021. Spectral Analysis of Vertical Temperature Profile Time-Series Data in Yellowstone Lake Sediments. Water Resources Research, 57(4), e2020WR028430. [https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR028430 doi: 10.1029/2020WR028430]. [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1029/2020WR028430 Open Access Article]</ref>. VFLUX analytical solutions are limited by subsurface heterogeneity and diurnal temperature signal strength<ref name=”Irvine2017b”/>. [https://data.usgs.gov/modelcatalog/model/82fe0c15-97f5-4f6a-b389-b90f9bad615e 1DTempPro] (Figure 4c) provides a graphical user interface (GUI) for numerical solutions to heat transport<ref>Koch, F. W., Voytek, E. B., Day-Lewis, F. D., Healy, R., Briggs, M. A., Werkema, D., Lane Jr., J. W., 2015. 1DTempPro: A Program for Analysis of Vertical One-Dimensional (1D) Temperature Profiles v2.0. U.S. Geological Survey Software Release. [http://dx.doi.org/10.5066/F76T0JQS doi: 10.5066/F76T0JQS]. [https://data.usgs.gov/modelcatalog/model/82fe0c15-97f5-4f6a-b389-b90f9bad615e Free Download from USGS]</ref> and does not depend on diurnal signals. Numerical models can produce more accurate flux estimates in the case of complex boundary conditions and abrupt changes in flux rates, but require significant user calibration efforts for longer time series<ref name=”McAliley2022”> McAliley, W. A., Day-Lewis, F. D., Rey, D., Briggs, M. A., Shapiro, A. M., Werkema, D., 2022. Application of Recursive Estimation to Heat Tracing for Groundwater/Surface-Water Exchange. Water Resources Research, 58(6), e2021WR030443. [https://doi.org/10.1029/2021WR030443 doi: 10.1029/2021WR030443]. [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1029/2021WR030443 Open Access Article]</ref>. A hybrid approach between the analytical and numerical solutions, known as [https://www.sciencebase.gov/catalog/item/60a55c71d34ea221ce48b9e7 tempest1d]<ref name=”McAliley2022”/> improves flux modeling with enhanced computational efficiency, resolution of abrupt changes, evaluation of complex boundary conditions, and uncertainty estimations with each step. This new state-space modeling approach uses recursive estimation techniques to automatically estimate highly dynamic vertical flux patterns ranging from sub-daily to seasonal time scales<ref name=”McAliley2022”/>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Electrical Conductivity (EC) Based Technologies===

| |

| − | The electrical conductivity (EC)-based technologies exploit contrasts in EC between surface water and groundwater<ref>Cox, M. H., Su, G. W., Constantz, J., 2007. Heat, Chloride, and Specific Conductance as Ground Water Tracers near Streams. Groundwater, 45(2), pp. 187–195. [https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6584.2006.00276.x doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6584.2006.00276.x].</ref>. EC-based technologies are mostly applied as characterization tools, although the opportunity to monitor GWSWE dynamics with one of these technologies does exist. With the exception of specific conductance probes, the technologies measure the bulk EC of sediments, which will often (but not always) reveal evidence of GWSWE.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Electrical conduction (i.e., the transport of charges) in the Earth occurs via the ions dissolved in groundwater, with an additional contribution from ions in the electrical double layer (known as surface conduction)<ref name=”Binley2020”>Binley, A., Slater, L., 2020. Resistivity and Induced Polarization: Theory and Applications to the Near-Surface Earth. Cambridge University Press. [https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108685955 doi: 10.1017/9781108685955].</ref>. In relatively fresh surface water environments, groundwater is typically more electrically conductive than surface water due to the higher ion concentrations in groundwater. In these settings, groundwater inputs may be identified as zones of higher bulk EC beneath the bed. In coastal settings where surface water is saline, inputs of relatively fresh groundwater will give rise to zones of lower conductivity. Whereas the temperature-based methods rely on point measurements at the location of the sensor, the EC-based technologies

| |

| − | (with the exception of point specific conductance measurements) incorporate inverse modeling to estimate distributions of EC away from the sensors and beneath the bed. Consequently, these technologies may also image losses of surface water to groundwater<ref>Johnson, T. C., Slater, L. D., Ntarlagiannis, D., Day-Lewis, F. D., Elwaseif, M., 2012. Monitoring Groundwater-Surface Water Interaction Using Time-Series and Time- Frequency Analysis of Transient Three-Dimensional Electrical Resistivity Changes. Water Resources Research, 48(7). [https://doi.org/10.1029/2012WR011893 doi: 10.1029/2012WR011893]. [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1029/2012WR011893 Open Access Article]</ref>. Another advantage is that they may provide information on structural controls on zones of focused GWSWE expressed at the surface. However, interpretation of EC patterns from these technologies is inherently uncertain due to the fact that (with the exception of specific conductance probes) the bulk EC of the sediments is measured. Variations in lithology (e.g., porosity, grain size distribution, which determine the strength of surface conduction) can be misinterpreted as variations in the ionic composition of groundwater.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ====Characterization Methods====

| |

| − | | |

| − | =====Specific Conductance Probes=====

| |

| − | The simplest EC-based technology is a specific conductance probe, which measures the specific conductance of water between a small pair of metal plates at the end of the sensor probe. Many commercially available water quality sensors have a specific conductance sensor and a temperature sensor integrated into a single probe (they often also measure other water quality parameters, including pH and dissolved oxygen (DO) content). These are direct sensing measurements with a small footprint (the size of the sensor), so this is usually a time-consuming, inefficient method for detecting GWSWE dynamics. Furthermore, the sampling volume of the measurement is small (on the order of a cubic centimeter or less), so the degree to which the spot measurement is representative of larger-scale hydrological exchanges is often uncertain. However, specific conductance sensor remains popular, especially when integrated with a point temperature sensor, such as the [https://clu-in.org/programs/21m2/navytools/gsw/#trident Trident Probe].

| |

| − | | |

| − | =====Frequency Domain Electromagnetic (EM) Sensing Systems=====

| |

| − | [[File:IeryFig5.png |thumb|600px|Figure 5. (a) FDEM survey path within a stream/drainage channel network bisecting a wetland complex experiencing localized upwelling of contaminated groundwater (b) operation of an FDEM sensor (Dualem 421S, Dualem, CA) in this shallow stream environment (c) resulting imaging of EC structure in the upper 6 m of streambed sediments. Variations in EC may result from changes in sediment texture that determine the location of focused GWSWE. Dataset acquired under ESTCP project ER21-5237.]]

| |

| − | Electromagnetic (EM) sensors non-invasively sense the bulk EC of sediments (a function of both fluid composition and lithology as mentioned above) by measuring eddy currents induced in conductors using time varying electric and magnetic fields based on the physics of electromagnetic induction. Modern EM systems can simultaneously image across a range of depths. Frequency domain EM (FDEM) instruments generate a current that varies sinusoidally with time at a fixed frequency that is selected on the basis of desired exploration depth and resolution. State of the art FDEM sensors use a combination of different coil separations and/or frequencies to resolve conductivity structure over a range of depths. These instruments typically provide high-resolution (sub-meter) information on the EC structure in the upper 5 m (approximately, depending on EC) of the subsurface. Measurements are non-invasively and continuously made, meaning that large areas can be quickly surveyed on foot (e.g., along a shoreline) or from a boat in shallow water (1 m or less deep), for example when pulled along a river or stream channel. The method can also be deployed effectively in wetlands (Figure 5). FDEM data are often presented in terms of variations in the raw measurements because apparent EC values do not represent the true EC of the subsurface. However, with the increasing popularity of sensors with combinations of coil separations, the datasets can be inverted to obtain a model of the distribution of the true EC of the subsurface on land or below a water layer. Inversion of FDEM datasets is usually performed as a series of one-dimensional (1D) models, constrained to have a limited variance from each other, to generate a pseudo-2D model of the subsurface. Open-source software, such as [https://hkex.gitlab.io/emagpy/ EMagPy]<ref>McLachlan, P., Blanchy, G., Binley, A., 2021. EMagPy: Open-Source Standalone Software for Processing, Forward Modeling and Inversion of Electromagnetic Induction Data. Computers and Geosciences, 146, 104561. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2020.104561 doi: 10.1016/j.cageo.2020.104561].</ref>, is freely available to manage, visualize and interpret FDEM datasets.

| |

| − | | |

| − | =====Time Domain EM Sensing Systems=====

| |

| − | Time domain EM (TEM) systems transmit a current that is abruptly shut off (reduced to zero), resulting in a transient current flow that propagates (with decaying amplitude) into the earth. The time-decaying voltage recorded in a receiver coil contains information on the EC variation with depth below the instrument. TEM systems specifically designed for waterborne surveys provide investigation depths up to 70 m (again depending on electrical conductivity)<ref>Lane Jr., J. W., Briggs, M. A., Maurya, P. K., White, E. A., Pedersen, J. B., Auken, E., Terry, N., Minsley, B., Kress, W., LeBlanc, D. R., Adams, R., Johnson, C. D., 2020. Characterizing the Diverse Hydrogeology Underlying Rivers and Estuaries Using New Floating Transient Electromagnetic Methodology. Science of the Total Environment, 740, 140074. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140074 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140074]. [https://pdf.sciencedirectassets.com/271800/1-s2.0-S0048969720X00313/1-s2.0-S0048969720335944/am.pdf?X-Amz-Security-Token=IQoJb3JpZ2luX2VjEFIaCXVzLWVhc3QtMSJIMEYCIQDZ%2B%2FCGoVTTeSPFPtk4OW69PC4KEHqVkJKlXr53AsvHdQIhAPZN6QAcBxRTVXEK7JzdlztbyC0YCiI8uy0GY9A0rXePKrwFCPr%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2FwEQBRoMMDU5MDAzNTQ2ODY1IgwE9HI9XVU0l%2BzWSuoqkAXE3X7NIZ%2F%2FdOJUm0fUfbE9sV8pySpOwYC0486IvtPPTBowSKFbx3vAcqacG%2B6VAiPUlQJIbXyY10TtNJIVamtrdqKawz6kL9JuuoFesHagWsbHUu8xE0ZcEoSRoD%2Btocg7XxHtfdRC0cEM%2F6VDcKQg1h4j4Ak%2FrS2SJAvt0OmlvNNIXEp87MhMP7VU%2BTm788JJKs2VDuRNaz%2BoQ4W%2FpXpB5PxIB%2FvW55DtjmdUOTGB0d5Kwq1QTrX0z02SD3GaQFHvVlmwVtNbswzqgzLA%2BiHzqG9ZzmEqxJL8%2F%2F%2F9ZYahtdXZPWTTF0MqwAjskmy7aZoqn6H7bhO4tmQpgFLcVhkufPQkObVxTmCcSOUweT6yHq1K%2FysQrY9ba%2F6qCVFR2AhCvccsn0jTPVeMDhUkP0EAOZt3d4JvL9ZvViFh4WLjM69jB%2BBqXyhUEsOdPVC76RMMYWYtEhJq6bFKyAKX6VwvOnzoIcHxVuxa0ulPfshyymwNyeyXF30xrWDyUU10W5mThgljbwI1WWPubRFDCKiyuaEAJfMNZCM8I%2B8DaFm4qEpqgzOu28W0GnHova%2BLNza5yTpmNGZDRstWNTTeaE4VhgBuaLUc6TB0j7sH9yO5q5UOTqv4GN3X6w5GG758i7TgnNQPV5yjG%2Foyl46OgsVbq8ALyKvSFNYJeDS0Hv1s7pbwGHKi%2F7kZoOo30oLpN%2F8m1n5HYj%2Bxz7nkgzB5z7aelBYZERf3TypQaXlRiS%2FLgiqi6KzAsAKo07Mjn0lZNmTCrb7nsf3dPh2phYcVSRjSSZ4qTzF02Jc1kSHWGgNrt%2BaGRj2p%2FyNI%2Fb3WrvXffMSJ%2FpJfWJofKMlQP96TWBJt2mRZ6F6U5gWE4J5Dn%2BI8HTDduaytBjqwAf%2FpCFEnbS3RfOQ64c16pUa%2BCsCwOWuWoxV7sDyHaPuoDmfpmHbBMMQaUKp4iqCrDesa1Np01xsxOW6dUEHE9A2SmIS0eRtttMuf%2ByCQL8dXg3e5ptGM9VNkwpflS2rEpCCyDWN0rWMs7Dkzw232XzO9kR6ZNO5BJnQy1SOqoYn9kBTbY%2F6C0Nw3rkFIi%2FFHjxdyHk7pO0jf4p5graNK2kOB54cXa5PY5OcRRcv2irwk&X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Date=20240120T014358Z&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Expires=300&X-Amz-Credential=ASIAQ3PHCVTY3WJS7ASS%2F20240120%2Fus-east-1%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Signature=5780b8a5381ef60b05df0e480b9c6d222c334b1d738bac8f9df7c3ae0b27fe59&hash=bcff28fddb45f4ac782f40fcc311db617d06d21300beb12018d4810d1baca112&host=68042c943591013ac2b2430a89b270f6af2c76d8dfd086a07176afe7c76c2c61&pii=S0048969720335944&tid=pdf-2543cf95-ab24-4e83-9d62-963bcb00db35&sid=27b3c4ac266c74410d0954f-878848e7f20agxrqa&type=client Open Access Manuscript]</ref>. Airborne TEM systems can also be deployed to look at large-scale surface water/groundwater dynamics, for example submarine discharge or saline intrusion along coastlines<ref>d’Ozouville, N., Auken, E., Sorensen, K., Violette, S., de Marsily, G., Deffontaines, B., Merlen, G., 2008. Extensive Perched Aquifer and Structural Implications Revealed by 3D Resistivity Mapping in a Galapagos Volcano. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 269(3–4), pp. 518–522. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2008.03.011 doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2008.03.011].</ref>. Inverse methods are employed to convert the raw measurements obtained along a transect into a distribution of conductivity.

| |

| − | | |

| − | =====Waterborne Electrical Imaging=====

| |

| − | [[File:IeryFig6.png |thumb|600px|left|Figure 6. Waterborne electrical imaging in a coastal setting with expected zones of upwelling groundwater (a) typical operation with floating electrode cable pulled behind boat (b) inverted 2D cross section of electrical resistivity along the survey path with possible zones of fresh groundwater discharges indicated from relatively high resistivity sediments. Dataset acquired under ESTCP project ER21-5237.]]

| |

| − | Electrical imaging techniques are based on galvanic (direct) contact between electrodes used to inject currents (and measure voltages) and the subsurface<ref name=”Binley2020”/>. Relative to EM methods, this can be a disadvantage when surveying on land. However, when making measurements from a water body, the electrodes used to acquire the data can be deployed as a floating array that is pulled behind a vessel. Waterborne electrical imaging relies on acquiring measurements of electrical potential differences between different pairs of electrodes on the array while current is passed between one pair of electrodes<ref>Day-Lewis, F. D., White, E. A., Johnson, C. D., Lane Jr, J. W., Belaval, M., 2006. Continuous Resistivity Profiling to Delineate Submarine Groundwater Discharge—Examples and Limitations. The Leading Edge, 25(6), pp. 724–728. [https://doi.org/10.1190/1.2210056 doi: 10.1190/1.2210056]</ref>. As the array is pulled behind the boat, thousands of measurements are made along a survey transect. Similar to the EM methods, inverse methods are used to process these datasets and generate a 2D image of the variation in the conductivity of the sediments below the bed. Open-source software such as [https://hkex.gitlab.io/resipy/ ResIPy] support 2D or 3D inversion of waterborne datasets. Figure 6 shows results of a waterborne electrical imaging survey conducted to locate regions where relative fresh (electrically resistive) groundwater is discharging into the near shore environment in a coastal setting. Beneath the saline (low resistivity) water layer, spatial variability in resistivity may partly be related to variations in the pore-filling fluid conductivity, with localized resistive zones possibly indicating upwelling fresh groundwater. However, the variation in resistivity in the sediments below the water layer may reflect variations in lithology. An extension of the electrical imaging method involves collecting induced polarization (IP) data<ref name=”Binley2020”/> in addition to electrical resistivity data. IP measurements capture the temporary charge storage characteristics of the subsurface, which are strongly controlled by lithology, with finer-grained (e.g. clay rich) sediments being more chargeable than coarser grained sediments. The method can be particularly useful for differentiating between conductivity variations resulting from variations in pore fluid specific conductance and those conductivity variations associated with lithology. For example, based on electrical imaging methods alone (or the EM method alone), it may not be possible to distinguish a zone of high specific conductance groundwater entering into freshwater from a region of relatively finer- grained sediments without additional supporting data (e.g. a core). IP measurements may be able to resolve this ambiguity as the region of finer-grained sediments will be more chargeable than the surrounding areas.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ====Monitoring Methods====

| |

| − | | |

| − | =====Land-based Electrical Monitoring=====

| |

| − | There is increasing interest in the use of electrical imaging methods as monitoring systems. Semi-permanent arrays of electrodes can be installed to monitor groundwater/surface water dynamics over periods of days to years. Low-power instrumentation has been developed to specifically address the needs for long-term monitoring, although such instrumentation is not yet commercially available. Consequently, electrical monitoring of groundwater/surface water interactions currently remains in the realm of the research-driven specialist.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Considerations for Using EM and Waterborne Electrical Imaging Methods===

| |

| − | The EM and waterborne electrical imaging methods both provide a way to determine variations in bulk electrical conductivity associated with groundwater/surface water interactions. However, each method has some advantages and some disadvantages. One consideration is maneuverability, particularly in shallow water environments. FDEM instruments are the most maneuverable, although they offer only limited investigation depths. Although bigger than the shallow-sensing frequency domain EM systems, TEM systems are still relatively maneuverable on water bodies. Whereas FDEM systems can be operated from a single small vessel, the TEM deployments require the use of pontoons as the transmitter and receiver coils need to be separated 9 m apart. This still equates to good maneuverability compared to waterborne electrical imaging where a floating electrode cable, typically 30-50 m long, is pulled behind a vessel.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In all three methods, variations in the water layer depth and the specific conductance of the water can significantly affect the data, especially in deeper water. Therefore, it is common to continuously record these parameters with an echo sounder and a specific conductance probe suspended in the water layer.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Other Hydrogeophysical Technologies===

| |

| − | A number of other hydrogeophysical technologies exist, with proven applications to the characterization of settings where GWSWE occurs. Seismic

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Hydroquinones have been widely used as surrogates to understand the reductive transformation of NACs and MCs by NOM. Figure 4 shows the chemical structures of the singly deprotonated forms of four hydroquinone species previously used to study NAC/MC reduction. The second-order rate constants (''k<sub>R</sub>'') for the reduction of NACs/MCs by these hydroquinone species are listed in Table 1, along with the aqueous-phase one electron reduction potentials of the NACs/MCs (''E<sub>H</sub><sup>1’</sup>'') where available. ''E<sub>H</sub><sup>1’</sup>'' is an experimentally measurable thermodynamic property that reflects the propensity of a given NAC/MC to accept an electron in water (''E<sub>H</sub><sup>1</sup>''(R-NO<sub>2</sub>)):

| |

| − | | |

| − | :::::<big>'''Equation 1:''' ''R-NO<sub>2</sub> + e<sup>-</sup> ⇔ R-NO<sub>2</sub><sup>•-</sup>''</big>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Knowing the identity of and reaction order in the reductant is required to derive the second-order rate constants listed in Table 1. This same reason limits the utility of reduction rate constants measured with complex carbonaceous reductants such as NOM<ref name="Dunnivant1992"/>, BC<ref name="Oh2013"/><ref name="Oh2009"/><ref name="Xu2015"/><ref name="Xin2021">Xin, D., 2021. Understanding the Electron Storage Capacity of Pyrogenic Black Carbon: Origin, Redox Reversibility, Spatial Distribution, and Environmental Applications. Doctoral Thesis, University of Delaware. [https://udspace.udel.edu/bitstream/handle/19716/30105/Xin_udel_0060D_14728.pdf?sequence=1 Free download.]</ref>, and HS<ref name="Luan2010"/><ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2021"/>, whose chemical structures and redox moieties responsible for the reduction, as well as their abundance, are not clearly defined or known. In other words, the observed rate constants in those studies are specific to the experimental conditions (e.g., pH and NOM source and concentration), and may not be easily comparable to other studies.

| |

| − | | |

| − | {| class="wikitable mw-collapsible" style="float:left; margin-right:40px; text-align:center;"

| |

| − | |+ Table 1. Aqueous phase one electron reduction potentials and logarithm of second-order rate constants for the reduction of NACs and MCs by the singly deprotonated form of the hydroquinones lawsone, juglone, AHQDS and AHQS, with the second-order rate constants for the deprotonated NAC/MC species (i.e., nitrophenolates and NTO<sup>–</sup>) in parentheses.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! Compound

| |

| − | ! rowspan="2" |''E<sub>H</sub><sup>1'</sup>'' (V)

| |

| − | ! colspan="4"| Hydroquinone [log ''k<sub>R</sub>'' (M<sup>-1</sup>s<sup>-1</sup>)]

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! (NAC/MC)

| |

| − | ! LAW<sup>-</sup>

| |

| − | ! JUG<sup>-</sup>

| |

| − | ! AHQDS<sup>-</sup>

| |

| − | ! AHQS<sup>-</sup>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | Nitrobenzene (NB) || -0.485<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.380<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -1.102<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 2.050<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || 3.060<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-nitrotoluene (2-NT) || -0.590<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -1.432<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -2.523<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.775<ref name="Hartenbach2008"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-nitrotoluene (3-NT) || -0.475<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.462<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -0.921<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-nitrotoluene (4-NT) || -0.500<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.041<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -1.292<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 1.822<ref name="Hartenbach2008"/> || 2.610<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-chloronitrobenzene (2-ClNB) || -0.485<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.342<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -0.824<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> ||2.412<ref name="Hartenbach2008"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-chloronitrobenzene (3-ClNB) || -0.405<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 1.491<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.114<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-chloronitrobenzene (4-ClNB) || -0.450<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 1.041<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -0.301<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 2.988<ref name="Hartenbach2008"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-acetylnitrobenzene (2-AcNB) || -0.470<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.519<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || -0.456<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-acetylnitrobenzene (3-AcNB) || -0.405<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 1.663<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 0.398<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-acetylnitrobenzene (4-AcNB) || -0.360<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 2.519<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || 1.477<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-nitrophenol (2-NP) || || 0.568 (0.079)<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) || || -0.699 (-1.301)<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-methyl-2-nitrophenol (4-Me-2-NP) || || 0.748 (0.176)<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-chloro-2-nitrophenol (4-Cl-2-NP) || || 1.602 (1.114)<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 5-fluoro-2-nitrophenol (5-Cl-2-NP) || || 0.447 (-0.155)<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/> || || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) || -0.280<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/> || || 2.869<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || 5.204<ref name="Hartenbach2008"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-amino-4,6-dinitrotoluene (2-A-4,6-DNT) || -0.400<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/> || || 0.987<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-amino-2,6-dinitrotoluene (4-A-2,6-DNT) || -0.440<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/> || || 0.079<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2,4-diamino-6-nitrotoluene (2,4-DA-6-NT) || -0.505<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/> || || -1.678<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2,6-diamino-4-nitrotoluene (2,6-DA-4-NT) || -0.495<ref name="Schwarzenbach2016"/> || || -1.252<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 1,3-dinitrobenzene (1,3-DNB) || -0.345<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || || 1.785<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 1,4-dinitrobenzene (1,4-DNB) || -0.257<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || || 3.839<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-nitroaniline (2-NANE) || < -0.560<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || || -2.638<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-nitroaniline (3-NANE) || -0.500<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || || -1.367<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 1,2-dinitrobenzene (1,2-DNB) || -0.290<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/> || || || 5.407<ref name="Hartenbach2008"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-nitroanisole (4-NAN) || || -0.661<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || || 1.220<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-amino-4-nitroanisole (2-A-4-NAN) || || -0.924<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || || 1.150<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || 2.190<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 4-amino-2-nitroanisole (4-A-2-NAN) || || || ||1.610<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || 2.360<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 2-chloro-4-nitroaniline (2-Cl-5-NANE) || || -0.863<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || || 1.250<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || 2.210<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | N-methyl-4-nitroaniline (MNA) || || -1.740<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || || -0.260<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/> || 0.692<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/>

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (NTO) || || || || 5.701 (1.914)<ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2021"/> ||

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX) || || || || -0.349<ref name="Kwon2008"/> ||

| |

| − | |}

| |

| | | | |

| − | [[File:AbioMCredFig5.png | thumb |500px|Figure 5. Relative reduction rate constants of the NACs/MCs listed in Table 1 for AHQDS<sup>–</sup>. Rate constants are compared with respect to RDX. Abbreviations of NACs/MCs as listed in Table 1.]] | + | ==PFAS Background== |

| − | Most of the current knowledge about MC degradation is derived from studies using NACs. The reduction kinetics of only four MCs, namely TNT, N-methyl-4-nitroaniline (MNA), NTO, and RDX, have been investigated with hydroquinones. Of these four MCs, only the reduction rates of MNA and TNT have been modeled<ref name="Hofstetter1999"/><ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2019"/><ref name="Riefler2000">Riefler, R.G., and Smets, B.F., 2000. Enzymatic Reduction of 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene and Related Nitroarenes: Kinetics Linked to One-Electron Redox Potentials. Environmental Science and Technology, 34(18), pp. 3900–3906. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es991422f DOI: 10.1021/es991422f]</ref><ref name="Salter-Blanc2015">Salter-Blanc, A.J., Bylaska, E.J., Johnston, H.J., and Tratnyek, P.G., 2015. Predicting Reduction Rates of Energetic Nitroaromatic Compounds Using Calculated One-Electron Reduction Potentials. Environmental Science and Technology, 49(6), pp. 3778–3786. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es505092s DOI: 10.1021/es505092s] [https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/es505092s Open access article.]</ref>.

| + | PFAS are a broad class of chemicals with highly variable chemical structures<ref>Moody, C.A., Field, J.A., 1999. Determination of Perfluorocarboxylates in Groundwater Impacted by Fire-Fighting Activity. Environmental Science and Technology, 33(16), pp. 2800-2806. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es981355+ doi: 10.1021/es981355+]</ref><ref name="MoodyField2000">Moody, C.A., Field, J.A., 2000. Perfluorinated Surfactants and the Environmental Implications of Their Use in Fire-Fighting Foams. Environmental Science and Technology, 34(18), pp. 3864-3870. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es991359u doi: 10.1021/es991359u]</ref><ref name="GlügeEtAl2020">Glüge, J., Scheringer, M., Cousins, I.T., DeWitt, J.C., Goldenman, G., Herzke, D., Lohmann, R., Ng, C.A., Trier, X., Wang, Z., 2020. An Overview of the Uses of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). Environmental Science: Processes and Impacts, 22(12), pp. 2345-2373. [https://doi.org/10.1039/D0EM00291G doi: 10.1039/D0EM00291G] [[Media: GlügeEtAl2020.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>. One characteristic feature of PFAS is that they are fluorosurfactants, distinct from more traditional hydrocarbon surfactants<ref name="MoodyField2000"/><ref name="Brusseau2018">Brusseau, M.L., 2018. Assessing the Potential Contributions of Additional Retention Processes to PFAS Retardation in the Subsurface. Science of The Total Environment, 613-614, pp. 176-185. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.065 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.065] [[Media: Brusseau2018.pdf | Open Access Manuscript]]</ref><ref>Dave, N., Joshi, T., 2017. A Concise Review on Surfactants and Its Significance. International Journal of Applied Chemistry, 13(3), pp. 663-672. [https://doi.org/10.37622/IJAC/13.3.2017.663-672 doi: 10.37622/IJAC/13.3.2017.663-672] [[Media: DaveJoshi2017.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref>García, R.A., Chiaia-Hernández, A.C., Lara-Martin, P.A., Loos, M., Hollender, J., Oetjen, K., Higgins, C.P., Field, J.A., 2019. Suspect Screening of Hydrocarbon Surfactants in Afffs and Afff-Contaminated Groundwater by High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Environmental Science and Technology, 53(14), pp. 8068-8077. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b01895 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b01895]</ref>. Fluorosurfactants typically have a fully or partially fluorinated, hydrophobic tail with ionic (cationic, zwitterionic, or anionic) head group that is hydrophilic<ref name="MoodyField2000"/><ref name="GlügeEtAl2020"/>. The hydrophobic tail and ionic head group mean PFAS are very stable at hydrophobic adsorption interfaces when present in the aqueous phase<ref>Krafft, M.P., Riess, J.G., 2015. Per- and Polyfluorinated Substances (PFASs): Environmental Challenges. Current Opinion in Colloid and Interface Science, 20(3), pp. 192-212. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cocis.2015.07.004 doi: 10.1016/j.cocis.2015.07.004]</ref>. Examples of these interfaces include naturally occurring organic matter in soils and the air-water interface in the vadose zone<ref>Schaefer, C.E., Culina, V., Nguyen, D., Field, J., 2019. Uptake of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances at the Air–Water Interface. Environmental Science and Technology, 53(21), pp. 12442-12448. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b04008 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b04008]</ref><ref>Lyu, Y., Brusseau, M.L., Chen, W., Yan, N., Fu, X., Lin, X., 2018. Adsorption of PFOA at the Air–Water Interface during Transport in Unsaturated Porous Media. Environmental Science and Technology, 52(14), pp. 7745-7753. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b02348 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b02348]</ref><ref>Costanza, J., Arshadi, M., Abriola, L.M., Pennell, K.D., 2019. Accumulation of PFOA and PFOS at the Air-Water Interface. Environmental Science and Technology Letters, 6(8), pp. 487-491. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.9b00355 doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.9b00355]</ref><ref>Li, F., Fang, X., Zhou, Z., Liao, X., Zou, J., Yuan, B., Sun, W., 2019. Adsorption of Perfluorinated Acids onto Soils: Kinetics, Isotherms, and Influences of Soil Properties. Science of The Total Environment, 649, pp. 504-514. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.209 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.209]</ref><ref>Nguyen, T.M.H., Bräunig, J., Thompson, K., Thompson, J., Kabiri, S., Navarro, D.A., Kookana, R.S., Grimison, C., Barnes, C.M., Higgins, C.P., McLaughlin, M.J., Mueller, J.F., 2020. Influences of Chemical Properties, Soil Properties, and Solution pH on Soil–Water Partitioning Coefficients of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs). Environmental Science and Technology, 54(24), pp. 15883-15892. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c05705 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c05705] [[Media: NguyenEtAl2020.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>. Their strong adsorption to both soil organic matter and the air-water interface is a major contributor to elevated concentrations of PFAS observed in the upper 5 feet of the soil column<ref name="BrusseauEtAl2020"/><ref name="BiglerEtAl2024"/>. While several other PFAS partitioning processes exist<ref name="Brusseau2018"/>, adsorption to solid phase soils and air-water interfaces are the two primary processes present at nearly all PFAS sites<ref>Brusseau, M.L., Yan, N., Van Glubt, S., Wang, Y., Chen, W., Lyu, Y., Dungan, B., Carroll, K.C., Holguin, F.O., 2019. Comprehensive Retention Model for PFAS Transport in Subsurface Systems. Water Research, 148, pp. 41-50. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2018.10.035 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.10.035]</ref>. The total PFAS mass obtained from a vadose zone soil sample contains the solid phase, air-water interfacial, and aqueous phase PFAS mass, which can be converted to porewater concentrations using Equation 1<ref name="BrusseauGuo2022"/>.</br> |

| | + | :: <big>'''Equation 1:'''</big> [[File: StultsEq1.png | 400 px]]</br> |

| | + | Where ''C<sub>p</sub>'' is the porewater concentration, ''C<sub>t</sub>'' is the total PFAS concentration, ''ρ<sub>b</sub>'' is the bulk density of the soil, ''θ<sub>w</sub>'' is the volumetric water content, ''R<sub>d</sub>'' is the PFAS retardation factor, ''K<sub>d</sub>'' is the solid phase adsorption coefficient, ''K<sub>ia</sub>'' is the air-water interfacial adsorption coefficient, and ''A<sub>aw</sub>'' is the air-water interfacial area. The air-water interfacial area of the soil is primarily a function of both the soil properties and the degree of volumetric water saturation in the soil. There are several methods of estimating air-water interfacial areas including thermodynamic functions based on the soil moisture retention curve. However, the thermodynamic function has been shown to underestimate air-water interfacial area<ref name="Brusseau2023">Brusseau, M.L., 2023. Determining Air-Water Interfacial Areas for the Retention and Transport of PFAS and Other Interfacially Active Solutes in Unsaturated Porous Media. Science of The Total Environment, 884, Article 163730. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.163730 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.163730] [[Media: Brusseau2023.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>, and must typically be scaled using empirical scaling factors. An empirical method recently developed to estimate air-water interfacial area is presented in Equation 2<ref name="Brusseau2023"/>.</br> |

| | + | :: <big>'''Equation 2:'''</big> [[File: StultsEq2.png | 400 px]]</br> |

| | + | Where ''S<sub>w</sub>'' is the water phase saturation as a ratio of the water content over the volumetric soil porosity, and ''d<sub>50</sub>'' is the median grain diameter. |

| | | | |

| − | Using the rate constants obtained with AHQDS<sup>–</sup>, a relative reactivity trend can be obtained (Figure 5). RDX is the slowest reacting MC in Table 1, hence it was selected to calculate the relative rates of reaction (i.e., log ''k<sub>NAC/MC</sub>'' – log ''k<sub>RDX</sub>''). If only the MCs in Figure 5 are considered, the reactivity spans 6 orders of magnitude following the trend: RDX ≈ MNA < NTO<sup>–</sup> < DNAN < TNT < NTO. The rate constant for DNAN reduction by AHQDS<sup>–</sup> is not yet published and hence not included in Table 1. Note that speciation of NACs/MCs can significantly affect their reduction rates. Upon deprotonation, the NAC/MC becomes negatively charged and less reactive as an oxidant (i.e., less prone to accept an electron). As a result, the second-order rate constant can decrease by 0.5-0.6 log unit in the case of nitrophenols and approximately 4 log units in the case of NTO (numbers in parentheses in Table 1)<ref name="Schwarzenbach1990"/><ref name="Murillo-Gelvez2021"/>.

| + | ==Lysimeters Background== |

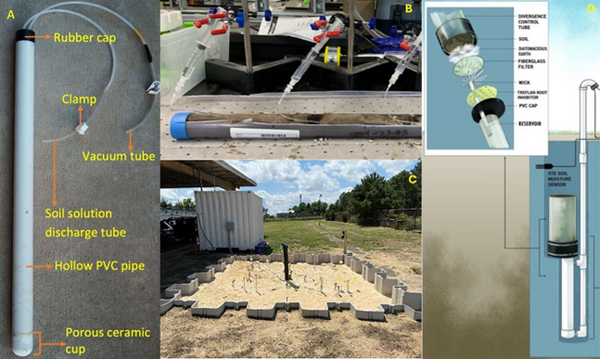

| | + | [[File: StultsFig1.png |thumb|600 px|Figure 1. (a) A field suction lysimeter with labeled parts typically used in field settings – Credit: Bibek Acharya and Dr. Vivek Sharma, UF/IFAS, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/AE581. (b) Laboratory suction lysimeters used in Schaefer ''et al.'' 2024<ref name="SchaeferEtAl2024"/>, which employed the use of micro-sampling suction lysimeters. (c) A field lysimeter used in Schaefer ''et al.'' 2023<ref name="SchaeferEtAl2023"/>. (d) Diagram of a drainage wicking lysimeter – Credit: Edaphic Scientific, https://edaphic.com.au/products/water/lysimeter-wick-for-drainage/]] |

| | + | Lysimeters, generally speaking, refer to instruments which collect water from unsaturated soils<ref name="MeissnerEtAl2020"/><ref name="RogersMcConnell1993"/>. However, there are multiple types of lysimeters which can be employed in field or laboratory settings. There are three primary types of lysimeters relevant to PFAS listed here and shown in Figure 1a-d. |