Munitions Constituents - Electrochemical Treatment

Electrochemical treatment of munitions constituents is an emerging technology for the remediation of explosive compounds in wastewater. This process utilizes electrochemical oxidation mechanisms to degrade both legacy explosives, as well as newer insensitive high explosives. The treatment relies on direct electron transfer reactions and the generation of highly reactive hydroxyl radicals at the electrode surface. Recent research has elucidated the oxidation pathways and byproducts for various munitions constituents, demonstrating the potential of electrochemical methods as an effective and environmentally friendly alternative to traditional adsorption-based treatments for explosive-contaminated water.

Related Article(s):

- Munitions Constituents

- Munitions Constituents - Abiotic Reduction

- Munitions Constituents - Alkaline Degradation

- Munitions Constituents – Photolysis

- Munitions Constituents - Sorption

Contributor(s): Dr. Brian P. Chaplin and S. M. Mohaiminul Islam

Key Resource(s):

- Electrochemical Destruction of Insensitive High Explosives Using Magnéli Phase Titanium Oxide Reactive Electrochemical Membranes[1]

- Electrochemical Method Applicable to Treatment of Wastewater from Nitrotriazolone Production[2]

- Efficient Removal of 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene (TNT) from Industrial/Military Wastewater Using Anodic Oxidation on Boron-Doped Diamond Electrodes[3]

- Treatment of High Explosive Production Wastewater Containing RDX by Combined Electrocatalytic Reaction and Anoxic–Oxic Biodegradation[4]

- Performance Optimization and Toxicity Effects of the Electrochemical Oxidation of Octogen[5]

Introduction

Munitions constituents refer to the energetic compounds utilized in various military applications, such as propellants, artillery shells, and ballistic agents. Legacy munitions constituents typically include compounds such as 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT), Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX), and 1,3,5,7-tetranitro-1,3,5,7-tetrazocane (HMX). However, due to safety concerns, there has been a shift towards the use of Insensitive High Explosives (IHEs). These compounds offer reduced susceptibility to unintended detonation, enhancing safety in military applications. One notable example of an IHE is IMX-101, a standard explosive formulation containing 2,4-dinitroanisole (DNAN), nitroguanidine (NQ), and 3-nitro-1-2-4-triazol-5-one (NTO).

Electrochemical Oxidation Mechanisms

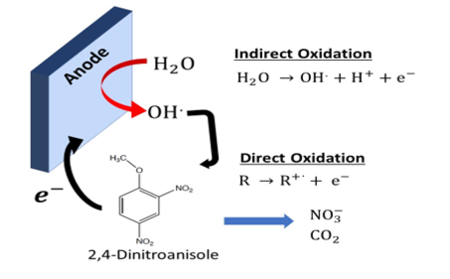

In electrochemical wastewater treatment, contaminants react either through a direct electron transfer (DET) reaction with the electrode or with a reactive species generated at the surface of the electrode (Figure 1)[6][7][8][9][10][11][12]. Electrochemical advanced oxidation process (EAOP) electrodes generally have a high overpotential for the oxygen evolution reaction, which allows them to produce hydroxyl radicals (OH•), a strong oxidant [E0(OH•/H2O) = 2.8 vs normal hydrogen electrode (NHE)][13], through water oxidation according to equation (1).

H2O → OH• + H+ + e- (1)

Then the contaminants (R) react with these electrochemically generated hydroxyl radicals (OH•) to form mineralization products according to reaction (2).

R + OH• → xHNO3 + yCO2 + zH2O (2)

In equation (2), x, y, and z represent stoichiometric ratios that are dependent on the composition of species R. The other primary oxidation is through the DET mechanism, according to reaction (3).

R → (R•)+ + e- (3)

Electrochemical Oxidation of Munitions

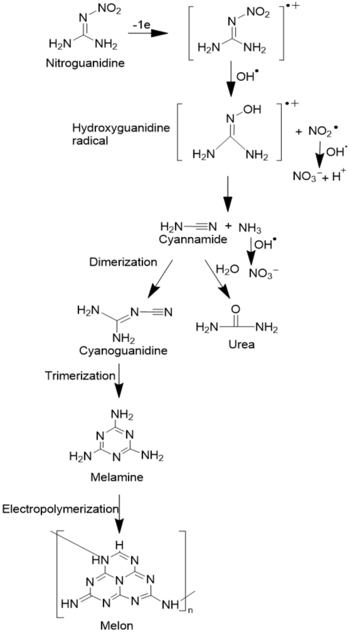

Nitroguanidine (NQ)

Electrochemical oxidation of NQ has been reported recently on a porous Ti4O7 electrode. Analysis by linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) revealed that NQ undergoes oxidation via a DET reaction[1]. Following the initial DET step, the resulting radical reacts with as shown in the pathway in Figure 2. Analysis of oxidation byproducts showed the formation of nitrate, cyanamide, urea, and melamine depending on the electrode potential. The nitrate yield was observed to be a function of the initial NQ concentration. Lower concentrations of NQ showed higher nitrate yield, whereas higher concentrations of NQ led to lower nitrate yield due to increased byproduct formation from elevated NQ concentration.

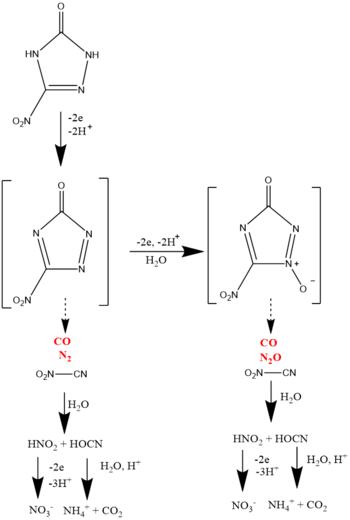

3-Nitro-1-2-4-triazol-5-one (NTO)

Studies from the literature showed that NTO undergoes electrochemical oxidation via a direct electron transfer mechanism, as studies conducted on a glassy carbon electrode showed an increase in current for NTO-spiked solutions[2]. A pathway for electrochemical oxidation of NTO has also been proposed (Figure 3). According to the proposed pathway, NTO forms 5-nitrotriazolinone in the initial step. Due to its unstable nature, it decomposes to form O2N-CN, CO and N2. The O2N-CN compound then hydrolyzes and forms HNO2 and HOCN. Additional hydrolysis products of nitrate and ammonium were also observed[2].

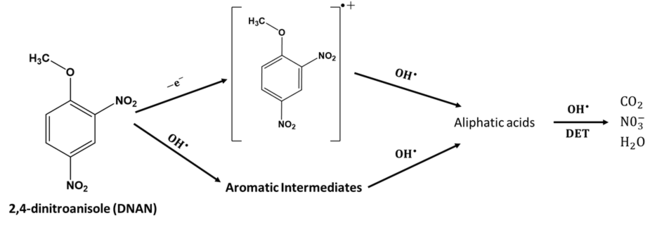

2,4-Dinitroanisole (DNAN)

Experimental and computational work has shown that DNAN can undergo both direct and indirect electrochemical oxidation[1][14][15]. Electrochemical oxidation of DNAN has produced nitrate, carbon dioxide, and water as the terminal byproducts[1]. DNAN can undergo direct oxidation on the anode as predicted by DFT calculations[1]. Moreover, it can also react with produced on the anode through addition and H atom abstraction mechanisms, ultimately leading to destabilization and ring-opening reactions[1][15]. The DNAN electrochemical oxidation pathway is shown in Figure 4.

2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene (TNT)

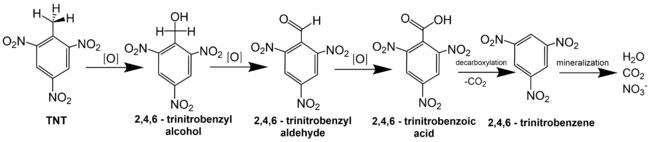

Electrochemical oxidation of TNT on a boron-doped-diamond (BDD) electrode was primarily attributed to H-atom abstraction reactions by OH•[3]. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry was used to identify the byproducts from TNT oxidation. Detection of compounds like trinitrobenzene and 1,3-dinitrobenzene supports the proposed pathway shown in Figure 5.

Hexahydro -1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX)

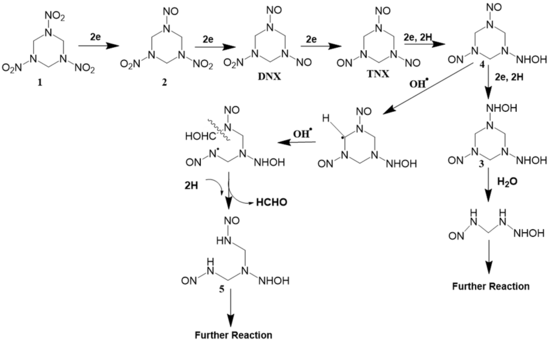

Electrochemical oxidation of RDX was studied on a TiO2-nantube/SnO2-Sb anode[4]. The proposed pathway (Figure 6) is based on synergistic electrochemical oxidation and reduction. RDX is first reduced to mono, di, and tri-nitroso RDX on the cathode based on the pathway. These intermediates are then attacked by OH• generated on the anode which leads to ring-opening reactions due to H abstraction by OH•. Formaldehyde, formic acid, nitrate, and nitrite were detected as terminal byproducts.

1,3,5,7-tetranitro-1,3,5,7-tetrazocane (HMX)

To date there is not any experimental evidence of HMX reacting through a direct electrochemical oxidation mechanism. However, some studies proposed that HMX reacted through indirect electrochemical oxidation[5][16]. The electrochemical oxidation pathway is driven by the reaction of RDX with electrochemically generated hydroxyl radicals through the addition mechanism (Figure 7). Detection of smaller compounds such as methylene dinitramine, urea, and acetamide provides support for this pathway.

Conclusion

Electrochemical oxidation of pollutants is a potentially effective technology using electrons as reactants, not requiring chemical dosage. It can be a viable alternative to adsorption-based methods for treating munitions constituents, eliminating the need for additional waste treatment and disposal.

References

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Islam, S.M.M., and Chaplin, B.P., 2024. Electrochemical Destruction of Insensitive High Explosives Using Magnéli Phase Titanium Oxide Reactive Electrochemical Membranes. ACS ES&T Engineering, 4(5), pp. 1241-1252. doi: 10.1021/acsestengg.3c00620

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Wallace, L., Cronin, M.P., Day, A.I., and Buck, D.P., 2009. Electrochemical Method Applicable to Treatment of Wastewater from Nitrotriazolone Production. Environmental Science & Technology, 43(6), pp. 1993-1998. doi: 10.1021/es8028878

- ^ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Szopińska, M., Prasuła, P., Baran, P., Kaczmarzyk, I., Pierpaoli, M., Nawała, J., Szala, M., Fudała-Książek, S., Kamieńska-Duda, A., and Dettlaff, A., 2024. Efficient Removal of 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene (TNT) from Industrial/Military Wastewater Using Anodic Oxidation on Boron-Doped Diamond Electrodes. Scientific Reports, 14, pp. 4802. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-55573-w Article pdf

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Chen, Y., Hong, L., Han, W., Wang, L., Sun, X., and Li, J., 2011. Treatment of High Explosive Production Wastewater Containing RDX by Combined Electrocatalytic Reaction and Anoxic–Oxic Biodegradation. Chemical Engineering Journal, 168(3), pp. 1256-1262. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2011.02.032

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Qian, Y., Chen, K., Chai, G., Xi, P., Yang, H., Xie, L., Qin, L., Lin, Y., Li, X., Yan, W., and Wang, D., 2022. Performance Optimization and Toxicity Effects of the Electrochemical Oxidation of Octogen. Catalysts, 12 (8), pp. 815. doi: 10.3390/catal12080815Article pdf

- ^ Comninellis, Ch., and Pulgarin, C., 1993. Electrochemical Oxidation of Phenol for Wastewater Treatment Using SnO2, Anodes. Journal of Applied Electrochemistry, 23 (2), pp. 108–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00246946

- ^ Borrás, C., Berzoy, C., Mostany, J., and Scharifker, B.R., 2006. Oxidation of P-Methoxyphenol on SnO2–Sb2O5 Electrodes: Effects of Electrode Potential and Concentration on the Mineralization Efficiency. Journal of Applied Electrochemistry, 36 (4), pp. 433–439. doi: 10.1007/s10800-005-9088-5

- ^ Borrás, C., Rodríguez, P., Laredo, T., Mostany, J., and Scharifker, B.R., 2004. Electrooxidation of Aqueous P-Methoxyphenol on Lead Oxide Electrodes. Journal of Applied Electrochemistry, 34 (6), pp. 583–589. doi: 10.1023/B:JACH.0000021922.73582.85

- ^ Borras, C., Laredo, T., and Scharifker, B.R., 2003. Competitive Electrochemical Oxidation of p-chlorophenol and p-nitrophenol on Bi-Doped PbO2. Electrochimica Acta, 48 (19), pp. 2775–2780. doi: 10.1016/S0013-4686(03)00411-0.

- ^ Kesselman, J. M., Weres, O., Lewis, N. S., and Hoffmann, M.R., 1997. Electrochemical Production of Hydroxyl Radical at Polycrystalline Nb-Doped TiO2 Electrodes and Estimation of the Partitioning between Hydroxyl Radical and Direct Hole Oxidation Pathways. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 101(14), pp. 2637–2643. doi: 10.1021/jp962669r.

- ^ Zaky, A.M., and Chaplin, B.P., 2013. Porous Substoichiometric TiO2 Anodes as Reactive Electrochemical Membranes for Water Treatment. Environmental Science & Technology, 47(12), pp. 6554–6563. doi: 10.1021/es401287e

- ^ Bejan, D., Guinea, E., and Bunce, N.J., 2012. On the Nature of the Hydroxyl Radicals Produced at Boron-Doped Diamond and Ebonex® Anodes. Electrochimica Acta, 69, pp. 275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2012.02.097.

- ^ Gligorovski, S., Strekowski, R., Barbati, S., and Vione, D., 2015. Environmental Implications of Hydroxyl Radicals (•OH). Chemical Reviews, 115(24), pp. 13051–13092. doi: 10.1021/cr500310b.

- ^ Zhou, Y., Liu, X., Jiang, W., and Shu, Y., 2018. Theoretical Insight into Reaction Mechanisms of 2,4-Dinitroanisole with Hydroxyl Radicals for Advanced Oxidation Processes. Journal of Molecular Modeling, 24 (2), pp. 44. doi: 10.1007/s00894-018-3580-4.

- ^ 15.0 15.1 Su, H., Christodoulatos, C., Smolinski, B., Arienti, P., O’Connor, G., and Meng, X., 2019. Advanced Oxidation Process for DNAN Using UV/H2O2. Engineering, 5(5), pp. 849–854. doi: 10.1016/j.eng.2019.08.003Article pdf

- ^ Bonin, P.M.L., Bejan, D., Radovic-Hrapovic, Z., Halasz, A., Hawari, J., and Bunce, N. J., 2005. Indirect Oxidation of RDX, HMX, and CL-20 Cyclic Nitramines in Aqueous Solution at Boron-Doped Diamond Electrodes. Environmental Chemistry, 2(2), pp. 125–129. doi: 10.1071/EN05006