Difference between revisions of "User:Jhurley/sandbox"

(→Application of High-Pressure Membranes for Treatment of PFAS Contaminated Water) |

(→Advantages) |

||

| (256 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | == | + | ==PFAS Destruction by Ultraviolet/Sulfite Treatment== |

| − | + | The ultraviolet (UV)/sulfite based reductive defluorination process has emerged as an effective and practical option for generating hydrated electrons (''e<sub><small>aq</small></sub><sup><big>'''-'''</big></sup>'' ) which can destroy [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) | PFAS]] in water. It offers significant advantages for PFAS destruction, including significant defluorination, high treatment efficiency for long-, short-, and ultra-short chain PFAS without mass transfer limitations, selective reactivity by hydrated electrons, low energy consumption, low capital and operation costs, and no production of harmful byproducts. A UV/sulfite treatment system designed and developed by Haley and Aldrich (EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor">Haley and Aldrich, Inc. (commercial business), 2024. EradiFluor. [https://www.haleyaldrich.com/about-us/applied-research-program/eradifluor/ Comercial Website]</ref>) has been demonstrated in two field demonstrations in which it achieved near-complete defluorination and greater than 99% destruction of 40 PFAS analytes measured by EPA method 1633. | |

<div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | ||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

*[[PFAS Ex Situ Water Treatment]] | *[[PFAS Ex Situ Water Treatment]] | ||

*[[PFAS Sources]] | *[[PFAS Sources]] | ||

| − | *[[PFAS | + | *[[PFAS Treatment by Electrical Discharge Plasma]] |

| + | *[[Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO)]] | ||

| + | *[[Photoactivated Reductive Defluorination - PFAS Destruction]] | ||

| − | '''Contributors:''' | + | '''Contributors:''' John Xiong, Yida Fang, Raul Tenorio, Isobel Li, and Jinyong Liu |

| − | '''Key | + | '''Key Resources:''' |

| − | + | *Defluorination of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) with Hydrated Electrons: Structural Dependence and Implications to PFAS Remediation and Management<ref name="BentelEtAl2019">Bentel, M.J., Yu, Y., Xu, L., Li, Z., Wong, B.M., Men, Y., Liu, J., 2019. Defluorination of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) with Hydrated Electrons: Structural Dependence and Implications to PFAS Remediation and Management. Environmental Science and Technology, 53(7), pp. 3718-28. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b06648 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b06648] [[Media: BentelEtAl2019.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref> | |

| − | * | + | *Accelerated Degradation of Perfluorosulfonates and Perfluorocarboxylates by UV/Sulfite + Iodide: Reaction Mechanisms and System Efficiencies<ref>Liu, Z., Chen, Z., Gao, J., Yu, Y., Men, Y., Gu, C., Liu, J., 2022. Accelerated Degradation of Perfluorosulfonates and Perfluorocarboxylates by UV/Sulfite + Iodide: Reaction Mechanisms and System Efficiencies. Environmental Science and Technology, 56(6), pp. 3699-3709. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c07608 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c07608] [[Media: LiuZEtAl2022.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref> |

| + | *Destruction of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) with UV-Sulfite Photoreductive Treatment<ref>Tenorio, R., Liu, J., Xiao, X., Maizel, A., Higgins, C.P., Schaefer, C.E., Strathmann, T.J., 2020. Destruction of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) with UV-Sulfite Photoreductive Treatment. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(11), pp. 6957-67. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c00961 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c00961]</ref> | ||

| + | *EradiFluor<sup>TM</sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> | ||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

| − | + | The hydrated electron (''e<sub><small>aq</small></sub><sup><big>'''-'''</big></sup>'' ) can be described as an electron in solution surrounded by a small number of water molecules<ref name="BuxtonEtAl1988">Buxton, G.V., Greenstock, C.L., Phillips Helman, W., Ross, A.B., 1988. Critical Review of Rate Constants for Reactions of Hydrated Electrons, Hydrogen Atoms and Hydroxyl Radicals (⋅OH/⋅O-) in Aqueous Solution. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 17(2), pp. 513-886. [https://doi.org/10.1063/1.555805 doi: 10.1063/1.555805]</ref>. Hydrated electrons can be produced by photoirradiation of solutes, including sulfite, iodide, dithionite, and ferrocyanide, and have been reported in literature to effectively decompose per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in water. The hydrated electron is one of the most reactive reducing species, with a standard reduction potential of about −2.9 volts. Though short-lived, hydrated electrons react rapidly with many species having more positive reduction potentials<ref name="BuxtonEtAl1988"/>. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Among the electron source chemicals, sulfite (SO<sub>3</sub><sup>2−</sup>) has emerged as one of the most effective and practical options for generating hydrated electrons to destroy PFAS in water. The mechanism of hydrated electron production in a sulfite solution under ultraviolet is shown in Equation 1 (UV is denoted as ''hv, SO<sub>3</sub><sup><big>'''•-'''</big></sup>'' is the sulfur trioxide radical anion): | |

| + | </br> | ||

| + | ::<big>'''Equation 1:'''</big> [[File: XiongEq1.png | 200 px]] | ||

| − | + | The hydrated electron has demonstrated excellent performance in destroying PFAS such as perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS)<ref>Gu, Y., Liu, T., Wang, H., Han, H., Dong, W., 2017. Hydrated Electron Based Decomposition of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) in the VUV/Sulfite System. Science of The Total Environment, 607-608, pp. 541-48. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.197 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.197]</ref> and GenX<ref>Bao, Y., Deng, S., Jiang, X., Qu, Y., He, Y., Liu, L., Chai, Q., Mumtaz, M., Huang, J., Cagnetta, G., Yu, G., 2018. Degradation of PFOA Substitute: GenX (HFPO–DA Ammonium Salt): Oxidation with UV/Persulfate or Reduction with UV/Sulfite? Environmental Science and Technology, 52(20), pp. 11728-34. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b02172 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b02172]</ref>. Mechanisms include cleaving carbon-to-fluorine (C-F) bonds (i.e., hydrogen/fluorine atom exchange) and chain shortening (i.e., decarboxylation, hydroxylation, elimination, and hydrolysis)<ref name="BentelEtAl2019"/>. | |

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | < | + | ==Process Description== |

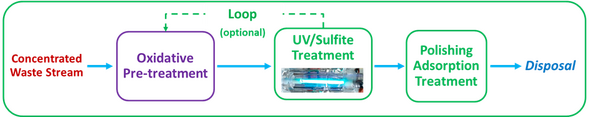

| − | + | A commercial UV/sulfite treatment system designed and developed by Haley and Aldrich (EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> includes an optional pre-oxidation step to transform PFAS precursors (when present) and treatment by UV/sulfite reduction to break C-F bonds. The effluent from the treatment process can be sent back to the influent of a pre-treatment separation system (such as a foam fractionation, regenerable ion exchange, or a membrane filtration system) for further concentration or sent for off-site disposal in accordance with relevant disposal regulations. A conceptual treatment process diagram is shown in Figure 1. [[File: XiongFig1.png | thumb | left | 600 px | Figure 1: Conceptual Treatment Process for a Concentrated PFAS Stream]] | |

| − | + | <br clear="left"/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Advantages== |

| + | A UV/sulfite treatment system offers significant advantages for PFAS destruction compared to other technologies, including high defluorination percentage, high treatment efficiency for short-chain PFAS without mass transfer limitation, selective reactivity by ''e<sub><small>aq</small></sub><sup><big>'''-'''</big></sup>'', low energy consumption, and the production of no harmful byproducts. A summary of these advantages is provided below: | ||

| + | *'''High efficiency for short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS:''' While the degradation efficiency for short-chain PFAS is challenging for some treatment technologies<ref>Singh, R.K., Brown, E., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holson, T.M., 2021. Treatment of PFAS-containing landfill leachate using an enhanced contact plasma reactor. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 408, Article 124452. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124452 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124452]</ref><ref>Singh, R.K., Multari, N., Nau-Hix, C., Woodard, S., Nickelsen, M., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holson, T.M., 2020. Removal of Poly- and Per-Fluorinated Compounds from Ion Exchange Regenerant Still Bottom Samples in a Plasma Reactor. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(21), pp. 13973-80. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c02158 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02158]</ref><ref>Nau-Hix, C., Multari, N., Singh, R.K., Richardson, S., Kulkarni, P., Anderson, R.H., Holsen, T.M., Mededovic Thagard S., 2021. Field Demonstration of a Pilot-Scale Plasma Reactor for the Rapid Removal of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Groundwater. American Chemical Society’s Environmental Science and Technology (ES&T) Water, 1(3), pp. 680-87. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestwater.0c00170 doi: 10.1021/acsestwater.0c00170]</ref>, the UV/sulfite process demonstrates excellent defluorination efficiency for both short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS, including trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and perfluoropropionic acid (PFPrA). | ||

| + | *'''High defluorination ratio:''' As shown in Figure 3, the UV/sulfite treatment system has demonstrated near 100% defluorination for various PFAS under both laboratory and field conditions. | ||

| + | *'''No harmful byproducts:''' | ||

| + | ==Analysis of PFAS Concentrations in Soil and Porewater== | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable mw-collapsible" style="float:left; margin-right:20px; text-align:center;" | ||

| + | |+Table 1. Measured and Predicted PFAS Concentrations in Porewater for Select PFAS in Three Different Soils | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !Site | ||

| + | !PFAS | ||

| + | !Field</br>Porewater</br>Concentration</br>(μg/L) | ||

| + | !Lab Core</br>Porewater</br>Concentration</br>(μg/L) | ||

| + | !Predicted</br>Porewater</br>Concentration</br>(μg/L) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Site A||PFOS||6.2 ± 3.4||3.0 ± 0.37||6.6 ± 3.3 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Site B||PFOS||2.2 ± 2.0||0.78 ± 0.38||2.8 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |rowspan="3"|Site C||PFOS||13 ± 4.1||680 ± 460||164 ± 75 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |8:2 FTS||1.2 ± 0.46||52 ± 13||16 ± 6.0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |PFHpS||0.36 ± 0.051||2.9 ± 2.0||5.9 ± 3.4 | ||

| + | |} | ||

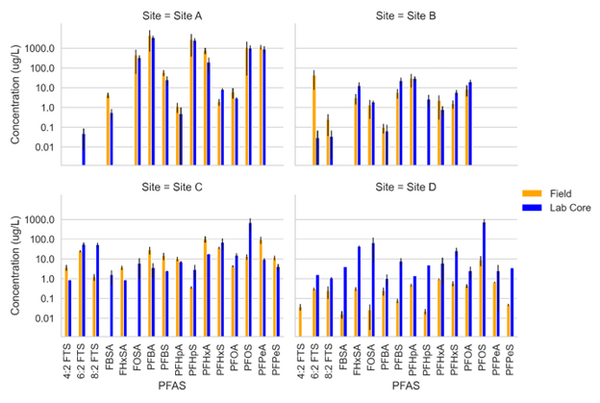

| + | [[File: StultsFig2.png | thumb | 600 px | Figure 2. Field Measured PFAS concentration Data (Orange) and Lab Core Measured Concentration Data (Blue) for four PFAS impacted sites<ref name="AndersonEtAl2022"/>]] | ||

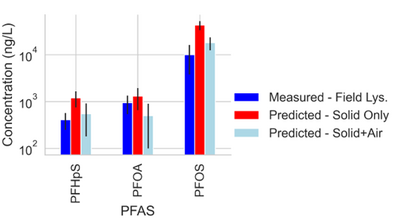

| + | [[File: StultsFig3.png | thumb | 400 px | Figure 3. Measured and predicted data for PFAS concentrations from a single site field lysimeter study. Model predictions both with and without PFAS sorption to the air-water interface were considered<ref name="SchaeferEtAl2023"/>.]] | ||

| + | Schaefer ''et al.''<ref name="SchaeferEtAl2024"/> measured PFAS porewater concentrations with field and laboratory suction lysimeters across several sites. Intact cores from the site were collected for soil water extraction using laboratory lysimeters. The lysimeters were used to directly compare field derived measurements of PFAS concentration in the mobile porewater phase. Results from measurements are for four sites presented in Figure 2. | ||

| − | + | Data from sites A and B showed reasonably good agreement (within ½ order of magnitude) for most PFAS measured in the systems. At site C, more hydrophobic constituents (> C6 PFAS) tended to have higher concentrations in the lab core than the field site while less hydrophobic constituents (< C6) had higher concentrations in the field than lab cores. Site D showed substantially greater (1 order of magnitude or more) PFAS concentrations measured in the laboratory-collected porewater sample compared to what was measured in the field lysimeters. This discrepancy for the Site D soil can likely be attributed to soil heterogeneity (as indicated by ground penetrating radar) and the fact that the soil consisted of back-filled materials rather than undisturbed native soils. | |

| + | |||

| + | Site C showed elevated PFAS concentrations in the laboratory collected porewater for the more surface-active compounds. This increase was attributed to the soil wetting that occurred at the bench scale, which was reasonably described by the model shown in Equations 1 and 2 (see Table 1<ref name="AndersonEtAl2022"/>). Equations 1 and 2 were also used to predict PFAS porewater concentrations (using porous cup lysimeters) in a highly instrumented test cell<ref name="SchaeferEtAl2023"/>(Figure 3). The ability to predict soil concentrations from recurring porewater samples is critical to the practical application of lysimeters in field settings<ref name="AndersonEtAl2022"/>. | ||

| − | + | Results from suction lysimeters studies and field lysimeter studies show that PFAS concentrations in porewater predicted from soil concentrations using Equations 1 and 2 generally have reasonable agreement with measured ''in situ'' porewater data when air-water interfacial partitioning is considered. Results show that for less hydrophobic components like PFOA, the impact of air-water interfacial adsorption is less significant than for highly hydrophobic components like PFOS. The soil for the field lysimeter in Figure 3 was a sandy soil with a relatively low air-water interfacial area. The effect of air-water interfacial partitioning is expected to be much more significant for a greater range of PFAS in soils with high capillary pressure (i.e. silts/clays) with higher associated air-water interfacial areas<ref name="Brusseau2023"/><ref>Peng, S., Brusseau, M.L., 2012. Air-Water Interfacial Area and Capillary Pressure: Porous-Medium Texture Effects and an Empirical Function. Journal of Hydrologic Engineering, 17(7), pp. 829-832. [https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)he.1943-5584.0000515 doi: 10.1061/(asce)he.1943-5584.0000515]</ref><ref>Brusseau, M.L., Peng, S., Schnaar, G., Costanza-Robinson, M.S., 2006. Relationships among Air-Water Interfacial Area, Capillary Pressure, and Water Saturation for a Sandy Porous Medium. Water Resources Research, 42(3), Article W03501, 5 pages. [https://doi.org/10.1029/2005WR004058 doi: 10.1029/2005WR004058] [[Media: BrusseauEtAl2006.pdf | Free Access Article]]</ref>. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Summary and Recommendations== | |

| + | The majority of research with lysimeters for PFAS site investigations has been done using porous cup suction lysimeters<ref name="CostanzaEtAl2025"/><ref name="AndersonEtAl2022"/><ref name="SchaeferEtAl2024"/><ref name="QuinnanEtAl2021"/>. Porous cup suction lysimeters are advantageous because they can be routinely sampled or sampled after specific wetting or drying events much like groundwater wells. This sampling is easier and more efficient than routinely collecting soil samples from the same locations. Co-locating lysimeters with soil samples is important for establishing the baseline soil concentration levels at the lysimeter location and developing correlations between the soil concentrations and the mobile porewater concentration<ref name="CostanzaEtAl2025"/>. Appropriate standard operation procedures for lysimeter installation and operation have been established and have been reviewed in recent literature<ref name="CostanzaEtAl2025"/><ref name="SchaeferEtAl2024"/>. Lysimeters should typically be installed near the source area and just above the maximum groundwater level elevation to obtain accurate results of porewater concentrations year round. Depending upon the geology and vertical PFAS distribution in the soil, multilevel lysimeter installations should also be considered. | ||

| − | + | Results from several lysimeters studies across multiple field sites and modelling analysis has shown that lysimeters can produce reasonable results between field and laboratory studies<ref name="SchaeferEtAl2024"/><ref name="SchaeferEtAl2023"/><ref name="SchaeferEtAl2022"/>. Transient effects of wetting and drying as well as media heterogeneity affects appear to be responsible for some variability and uncertainty in lysimeter based PFAS measurements in the vadose zone. These mobile porewater concentrations can be coupled with effective recharge estimates and simplified modelling approaches to determine mass flux from the vadose zone to the underlying groundwater<ref name="Anderson2021"/><ref name="StultsEtAl2024"/><ref name="BrusseauGuo2022"/><ref>Stults, J.F., Schaefer, C.E., MacBeth, T., Fang, Y., Devon, J., Real, I., Liu, F., Kosson, D., Guelfo, J.L., 2025. Laboratory Validation of a Simplified Model for Estimating Equilibrium PFAS Mass Leaching from Unsaturated Soils. Science of The Total Environment, 970, Article 179036. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2025.179036 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2025.179036]</ref><ref>Smith, J. Brusseau, M.L., Guo, B., 2024. An Integrated Analytical Modeling Framework for Determining Site-Specific Soil Screening Levels for PFAS. Water Research, 252, Article121236. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2024.121236 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2024.121236]</ref>. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Future research opportunities should address the current key uncertainties related to the use of lysimeters for PFAS investigations, including: | |

| + | #<u>Collect larger datasets of PFAS concentrations</u> to determine how transient wetting or drying periods and media type affect PFAS concentrations in the mobile porewater. Some research has shown that non-equilibrium processes can occur in the vadose zone, which can affect grab sample concentration in the porewater at specific time periods. | ||

| + | #<u>More work should be done with flux averaging lysimeters</u> like the drainage cup or wicking lysimeter. These lysimeters can directly measure net recharge and provide time averaged concentrations of PFAS in water over the sampling period. However, there is little work detailing their potential applications in PFAS research, or operational considerations for their use in remedial investigations for PFAS. | ||

| + | #<u>Lysimeters should be coupled with monitoring of wetting and drying</u> in the vadose zone using ''in situ'' soil moisture sensors or tensiometers and groundwater levels. Direct measurements of soil saturation at field sites are vital to directly correlate porewater concentrations with soil concentrations. Similarly, groundwater level fluctuations can inform net recharge estimates. By collecting these data we can continue to improve partitioning and leaching models which can relate porewater concentrations to total PFAS mass in soils and PFAS leaching at field sites. | ||

| + | #<u>Comparisons of various bench-scale leaching or desorption tests to field-based lysimeter data</u> are recommended. The ability to correlate field measurements of PFAS concentrations with estimates of leaching from laboratory studies would provide a powerful method to empirically estimate PFAS leaching from field sites. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Latest revision as of 19:44, 28 January 2026

PFAS Destruction by Ultraviolet/Sulfite Treatment

The ultraviolet (UV)/sulfite based reductive defluorination process has emerged as an effective and practical option for generating hydrated electrons (eaq- ) which can destroy PFAS in water. It offers significant advantages for PFAS destruction, including significant defluorination, high treatment efficiency for long-, short-, and ultra-short chain PFAS without mass transfer limitations, selective reactivity by hydrated electrons, low energy consumption, low capital and operation costs, and no production of harmful byproducts. A UV/sulfite treatment system designed and developed by Haley and Aldrich (EradiFluorTM[1]) has been demonstrated in two field demonstrations in which it achieved near-complete defluorination and greater than 99% destruction of 40 PFAS analytes measured by EPA method 1633.

Related Article(s):

- Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

- PFAS Ex Situ Water Treatment

- PFAS Sources

- PFAS Treatment by Electrical Discharge Plasma

- Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO)

- Photoactivated Reductive Defluorination - PFAS Destruction

Contributors: John Xiong, Yida Fang, Raul Tenorio, Isobel Li, and Jinyong Liu

Key Resources:

- Defluorination of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) with Hydrated Electrons: Structural Dependence and Implications to PFAS Remediation and Management[2]

- Accelerated Degradation of Perfluorosulfonates and Perfluorocarboxylates by UV/Sulfite + Iodide: Reaction Mechanisms and System Efficiencies[3]

- Destruction of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) with UV-Sulfite Photoreductive Treatment[4]

- EradiFluorTM[1]

Introduction

The hydrated electron (eaq- ) can be described as an electron in solution surrounded by a small number of water molecules[5]. Hydrated electrons can be produced by photoirradiation of solutes, including sulfite, iodide, dithionite, and ferrocyanide, and have been reported in literature to effectively decompose per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in water. The hydrated electron is one of the most reactive reducing species, with a standard reduction potential of about −2.9 volts. Though short-lived, hydrated electrons react rapidly with many species having more positive reduction potentials[5].

Among the electron source chemicals, sulfite (SO32−) has emerged as one of the most effective and practical options for generating hydrated electrons to destroy PFAS in water. The mechanism of hydrated electron production in a sulfite solution under ultraviolet is shown in Equation 1 (UV is denoted as hv, SO3•- is the sulfur trioxide radical anion):

The hydrated electron has demonstrated excellent performance in destroying PFAS such as perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS)[6] and GenX[7]. Mechanisms include cleaving carbon-to-fluorine (C-F) bonds (i.e., hydrogen/fluorine atom exchange) and chain shortening (i.e., decarboxylation, hydroxylation, elimination, and hydrolysis)[2].

Process Description

A commercial UV/sulfite treatment system designed and developed by Haley and Aldrich (EradiFluorTM[1] includes an optional pre-oxidation step to transform PFAS precursors (when present) and treatment by UV/sulfite reduction to break C-F bonds. The effluent from the treatment process can be sent back to the influent of a pre-treatment separation system (such as a foam fractionation, regenerable ion exchange, or a membrane filtration system) for further concentration or sent for off-site disposal in accordance with relevant disposal regulations. A conceptual treatment process diagram is shown in Figure 1.

Advantages

A UV/sulfite treatment system offers significant advantages for PFAS destruction compared to other technologies, including high defluorination percentage, high treatment efficiency for short-chain PFAS without mass transfer limitation, selective reactivity by eaq-, low energy consumption, and the production of no harmful byproducts. A summary of these advantages is provided below:

- High efficiency for short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS: While the degradation efficiency for short-chain PFAS is challenging for some treatment technologies[8][9][10], the UV/sulfite process demonstrates excellent defluorination efficiency for both short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS, including trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and perfluoropropionic acid (PFPrA).

- High defluorination ratio: As shown in Figure 3, the UV/sulfite treatment system has demonstrated near 100% defluorination for various PFAS under both laboratory and field conditions.

- No harmful byproducts:

Analysis of PFAS Concentrations in Soil and Porewater

| Site | PFAS | Field Porewater Concentration (μg/L) |

Lab Core Porewater Concentration (μg/L) |

Predicted Porewater Concentration (μg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site A | PFOS | 6.2 ± 3.4 | 3.0 ± 0.37 | 6.6 ± 3.3 |

| Site B | PFOS | 2.2 ± 2.0 | 0.78 ± 0.38 | 2.8 |

| Site C | PFOS | 13 ± 4.1 | 680 ± 460 | 164 ± 75 |

| 8:2 FTS | 1.2 ± 0.46 | 52 ± 13 | 16 ± 6.0 | |

| PFHpS | 0.36 ± 0.051 | 2.9 ± 2.0 | 5.9 ± 3.4 |

Schaefer et al.[13] measured PFAS porewater concentrations with field and laboratory suction lysimeters across several sites. Intact cores from the site were collected for soil water extraction using laboratory lysimeters. The lysimeters were used to directly compare field derived measurements of PFAS concentration in the mobile porewater phase. Results from measurements are for four sites presented in Figure 2.

Data from sites A and B showed reasonably good agreement (within ½ order of magnitude) for most PFAS measured in the systems. At site C, more hydrophobic constituents (> C6 PFAS) tended to have higher concentrations in the lab core than the field site while less hydrophobic constituents (< C6) had higher concentrations in the field than lab cores. Site D showed substantially greater (1 order of magnitude or more) PFAS concentrations measured in the laboratory-collected porewater sample compared to what was measured in the field lysimeters. This discrepancy for the Site D soil can likely be attributed to soil heterogeneity (as indicated by ground penetrating radar) and the fact that the soil consisted of back-filled materials rather than undisturbed native soils.

Site C showed elevated PFAS concentrations in the laboratory collected porewater for the more surface-active compounds. This increase was attributed to the soil wetting that occurred at the bench scale, which was reasonably described by the model shown in Equations 1 and 2 (see Table 1[11]). Equations 1 and 2 were also used to predict PFAS porewater concentrations (using porous cup lysimeters) in a highly instrumented test cell[12](Figure 3). The ability to predict soil concentrations from recurring porewater samples is critical to the practical application of lysimeters in field settings[11].

Results from suction lysimeters studies and field lysimeter studies show that PFAS concentrations in porewater predicted from soil concentrations using Equations 1 and 2 generally have reasonable agreement with measured in situ porewater data when air-water interfacial partitioning is considered. Results show that for less hydrophobic components like PFOA, the impact of air-water interfacial adsorption is less significant than for highly hydrophobic components like PFOS. The soil for the field lysimeter in Figure 3 was a sandy soil with a relatively low air-water interfacial area. The effect of air-water interfacial partitioning is expected to be much more significant for a greater range of PFAS in soils with high capillary pressure (i.e. silts/clays) with higher associated air-water interfacial areas[14][15][16].

Summary and Recommendations

The majority of research with lysimeters for PFAS site investigations has been done using porous cup suction lysimeters[17][11][13][18]. Porous cup suction lysimeters are advantageous because they can be routinely sampled or sampled after specific wetting or drying events much like groundwater wells. This sampling is easier and more efficient than routinely collecting soil samples from the same locations. Co-locating lysimeters with soil samples is important for establishing the baseline soil concentration levels at the lysimeter location and developing correlations between the soil concentrations and the mobile porewater concentration[17]. Appropriate standard operation procedures for lysimeter installation and operation have been established and have been reviewed in recent literature[17][13]. Lysimeters should typically be installed near the source area and just above the maximum groundwater level elevation to obtain accurate results of porewater concentrations year round. Depending upon the geology and vertical PFAS distribution in the soil, multilevel lysimeter installations should also be considered.

Results from several lysimeters studies across multiple field sites and modelling analysis has shown that lysimeters can produce reasonable results between field and laboratory studies[13][12][19]. Transient effects of wetting and drying as well as media heterogeneity affects appear to be responsible for some variability and uncertainty in lysimeter based PFAS measurements in the vadose zone. These mobile porewater concentrations can be coupled with effective recharge estimates and simplified modelling approaches to determine mass flux from the vadose zone to the underlying groundwater[20][21][22][23][24].

Future research opportunities should address the current key uncertainties related to the use of lysimeters for PFAS investigations, including:

- Collect larger datasets of PFAS concentrations to determine how transient wetting or drying periods and media type affect PFAS concentrations in the mobile porewater. Some research has shown that non-equilibrium processes can occur in the vadose zone, which can affect grab sample concentration in the porewater at specific time periods.

- More work should be done with flux averaging lysimeters like the drainage cup or wicking lysimeter. These lysimeters can directly measure net recharge and provide time averaged concentrations of PFAS in water over the sampling period. However, there is little work detailing their potential applications in PFAS research, or operational considerations for their use in remedial investigations for PFAS.

- Lysimeters should be coupled with monitoring of wetting and drying in the vadose zone using in situ soil moisture sensors or tensiometers and groundwater levels. Direct measurements of soil saturation at field sites are vital to directly correlate porewater concentrations with soil concentrations. Similarly, groundwater level fluctuations can inform net recharge estimates. By collecting these data we can continue to improve partitioning and leaching models which can relate porewater concentrations to total PFAS mass in soils and PFAS leaching at field sites.

- Comparisons of various bench-scale leaching or desorption tests to field-based lysimeter data are recommended. The ability to correlate field measurements of PFAS concentrations with estimates of leaching from laboratory studies would provide a powerful method to empirically estimate PFAS leaching from field sites.

References

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Haley and Aldrich, Inc. (commercial business), 2024. EradiFluor. Comercial Website

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Bentel, M.J., Yu, Y., Xu, L., Li, Z., Wong, B.M., Men, Y., Liu, J., 2019. Defluorination of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) with Hydrated Electrons: Structural Dependence and Implications to PFAS Remediation and Management. Environmental Science and Technology, 53(7), pp. 3718-28. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b06648 Open Access Article

- ^ Liu, Z., Chen, Z., Gao, J., Yu, Y., Men, Y., Gu, C., Liu, J., 2022. Accelerated Degradation of Perfluorosulfonates and Perfluorocarboxylates by UV/Sulfite + Iodide: Reaction Mechanisms and System Efficiencies. Environmental Science and Technology, 56(6), pp. 3699-3709. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c07608 Open Access Article

- ^ Tenorio, R., Liu, J., Xiao, X., Maizel, A., Higgins, C.P., Schaefer, C.E., Strathmann, T.J., 2020. Destruction of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) with UV-Sulfite Photoreductive Treatment. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(11), pp. 6957-67. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c00961

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Buxton, G.V., Greenstock, C.L., Phillips Helman, W., Ross, A.B., 1988. Critical Review of Rate Constants for Reactions of Hydrated Electrons, Hydrogen Atoms and Hydroxyl Radicals (⋅OH/⋅O-) in Aqueous Solution. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 17(2), pp. 513-886. doi: 10.1063/1.555805

- ^ Gu, Y., Liu, T., Wang, H., Han, H., Dong, W., 2017. Hydrated Electron Based Decomposition of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) in the VUV/Sulfite System. Science of The Total Environment, 607-608, pp. 541-48. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.197

- ^ Bao, Y., Deng, S., Jiang, X., Qu, Y., He, Y., Liu, L., Chai, Q., Mumtaz, M., Huang, J., Cagnetta, G., Yu, G., 2018. Degradation of PFOA Substitute: GenX (HFPO–DA Ammonium Salt): Oxidation with UV/Persulfate or Reduction with UV/Sulfite? Environmental Science and Technology, 52(20), pp. 11728-34. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b02172

- ^ Singh, R.K., Brown, E., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holson, T.M., 2021. Treatment of PFAS-containing landfill leachate using an enhanced contact plasma reactor. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 408, Article 124452. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124452

- ^ Singh, R.K., Multari, N., Nau-Hix, C., Woodard, S., Nickelsen, M., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holson, T.M., 2020. Removal of Poly- and Per-Fluorinated Compounds from Ion Exchange Regenerant Still Bottom Samples in a Plasma Reactor. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(21), pp. 13973-80. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02158

- ^ Nau-Hix, C., Multari, N., Singh, R.K., Richardson, S., Kulkarni, P., Anderson, R.H., Holsen, T.M., Mededovic Thagard S., 2021. Field Demonstration of a Pilot-Scale Plasma Reactor for the Rapid Removal of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Groundwater. American Chemical Society’s Environmental Science and Technology (ES&T) Water, 1(3), pp. 680-87. doi: 10.1021/acsestwater.0c00170

- ^ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedAndersonEtAl2022 - ^ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedSchaeferEtAl2023 - ^ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedSchaeferEtAl2024 - ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedBrusseau2023 - ^ Peng, S., Brusseau, M.L., 2012. Air-Water Interfacial Area and Capillary Pressure: Porous-Medium Texture Effects and an Empirical Function. Journal of Hydrologic Engineering, 17(7), pp. 829-832. doi: 10.1061/(asce)he.1943-5584.0000515

- ^ Brusseau, M.L., Peng, S., Schnaar, G., Costanza-Robinson, M.S., 2006. Relationships among Air-Water Interfacial Area, Capillary Pressure, and Water Saturation for a Sandy Porous Medium. Water Resources Research, 42(3), Article W03501, 5 pages. doi: 10.1029/2005WR004058 Free Access Article

- ^ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedCostanzaEtAl2025 - ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedQuinnanEtAl2021 - ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedSchaeferEtAl2022 - ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedAnderson2021 - ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedStultsEtAl2024 - ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedBrusseauGuo2022 - ^ Stults, J.F., Schaefer, C.E., MacBeth, T., Fang, Y., Devon, J., Real, I., Liu, F., Kosson, D., Guelfo, J.L., 2025. Laboratory Validation of a Simplified Model for Estimating Equilibrium PFAS Mass Leaching from Unsaturated Soils. Science of The Total Environment, 970, Article 179036. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2025.179036

- ^ Smith, J. Brusseau, M.L., Guo, B., 2024. An Integrated Analytical Modeling Framework for Determining Site-Specific Soil Screening Levels for PFAS. Water Research, 252, Article121236. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2024.121236